In Part 1 of this series I argued that school is essential because it provides structured and equitable access to humanity’s accumulated cultural knowledge, allowing each generation to build on the discoveries of the past rather than start from scratch. Through gene-culture coevolution, our brains have evolved to learn from others, making schools the most effective way to transmit this shared knowledge. In Part 2 I explored how our brains have evolved to easily acquire “biologically primary” knowledge which supports survival and develops instinctively. In contrast, “biologically secondary” knowledge is culturally acquired and must be explicitly taught. This distinction highlights the role of schools in focusing on this secondary knowledge, as trying to formally teach primary skills wastes time and may deepen inequality.

Education is a technology that tries to make up for what the human mind is innately bad at.

Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate

Although schools are an important technological invention, it’s not clear whether anyone ever sat down and dreamed up the idea of a school. It’s more likely that schools, along with many other aspects of human culture, emerged as the most effective way to pass on biologically secondary knowledge. Children don’t need to go to school to learn how to walk, talk, recognise objects or remember the personalities of their friends, even though these things are much harder than reading, adding or remembering dates in history. This is Moravec’s paradox: contrary to the initial expectations of artificial intelligence researchers, robots and computers are excellent at learning how to do many of the things we’re bad at, but – thus far – have struggled to learn those things we find easy.

David Geary tells us that “In contrast to universal folk knowledge, most of the knowledge taught in modern schools is culturally specific; that is, it does not emerge in the absence of formal instruction.” Schools emerged to teach those things children won’t learn elsewhere. We send children to school to learn written language, arithmetic and science because these bodies of knowledge were invented far too recently for any species-wide knack for acquiring them to have evolved, even if such a mechanism could arise through natural selection.

Think about the example of language. In The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker argues that we have an instinct for learning our mother tongue. Children’s ability to intuit previously unheard structures and formulations from minimal grammatical knowledge is remarkable. For instance, when learning English, most children infer that the past tense of the verb to go is ‘goed’. But how? No adult ever says this; children independently work out the rule that you add ‘ed’ to the end of the verb to indicate that it happened in the past. It’s only later that children learn that ‘to go’ is an irregular verb and ‘went’ is the correct formulation. This is just one of many thousands of examples which makes it clear that we have an instinct for learning language but specific vocabulary must be acquired the hard way. Compare this to the way we learn to read and write. While human beings have been using spoken language for tens of thousands of years, writing is a relatively recent invention. It’s only been in the past few hundred years that it’s been considered important for a majority of people to learn to read and write. As such, it should be clear that we can have no evolved instinct for written language in the way that we do for spoken language.

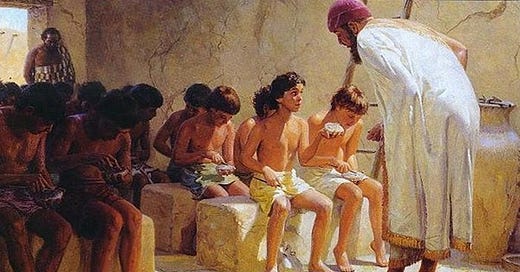

Schools – institutions for providing formal instruction in skills young people would not otherwise acquire – have only existed in literate cultures where biologically secondary knowledge has outstripped universal folk knowledge. If we look at ancient Sumer where cuneiform, the earliest known writing system developed, we also find the first archaeological evidence of schools, which were set up to induct budding clerks into the mystery of scribing. These edubas (scribe schools) were probably fairly informal, usually taking place in private homes, but some sites, where particularly large numbers of school tablets have been unearthed, are considered by archaeologists to be ‘school houses’. We know a surprising amount about how edubas operated as various cuneiform tablets contain stories attesting to what life was like as a scribal student.

Sumerian students began their education as young children, and although most students were boys, there is also evidence of some female scribes. The eduba literature paints a vivid picture of daily life for these young students. Lessons included reciting texts learned previously and forming new tablets to inscribe. Punishments for misbehaviour – talking out of turn, leaving without permission, writing poorly and so on – could be harsh. In one account, a student describes being beaten no less than seven times in a single day:

The door monitor said, ‘Why did you go out without my say-so?’ He beat me. The jug monitor said, ‘Why did you take beer without my say-so?’ He beat me. The Sumerian monitor said, ‘You spoke in Akkadian!’ He beat me. My teacher said, ‘Your handwriting is not at all good!’ He beat me.

And so on. Then, after a day at school, the students would return home to their parents, where they might have to recite homework assignments. Charmingly, there is even evidence of Sumerian teachers complaining about their students and students about their teachers.2

It was ever thus. In the 11th century, Egbert of Liege noted that, “Scholarly effort is in decline everywhere as never before. Indeed, cleverness is shunned at home and abroad. What does reading offer to pupils except tears? It is rare, worthless when it is offered for sale, and devoid of wit.”3 A 14th century student at the University of Bologna moaned that other students “attend classes but make no effort to learn anything … The expense money which they have from their parents or churches they spend in taverns, conviviality, games and other superfluities, and so they return home empty, without knowledge, conscience, or money.”4 And, in a letter from a 10th century Byzantine scholar to the father of some of his students:

I hesitated whether to write to you or not but decided that I ought. Children naturally prefer play to study: fathers naturally train them to follow good courses, using persuasion or force. Your children, like their companions, neglected their work and were in need of correction. I resolved to punish them, and to inform their father. They returned to work and studied for some time. But they are now occupied with birds once again, and neglecting their studies. Their father, passing through the city, commented acidly on their conduct. Instead of coming to me, or to their uncles, they have run away to you or to Olympus. If they are with you, treat them mercifully as suppliants. Even if they have gone elsewhere, help them return to the fold. You will have my gratitude.5

Why is it that education appears always to have had this effect on young people? Some commentators suppose the fault to be with the way schools operate and express despair that they have not moved with the times. It is, psychologist Douglas Detterman says, “a sad commentary on education” that the only educational innovations of note have been printed books and the blackboard:

If Plato or Aristotle walked into any classroom in any school, college, or university they would know exactly what was going on and could probably take over teaching the class (assuming they had a translator). They would certainly be amazed by the extent of what has been learned since their deaths but not at how it is taught.

Douglas K. Detterman, Education and Intelligence: Pity the Poor Teacher Because Student Characteristics are More Significant Than Teachers or Schools

Should we be amazed that the way children are taught today hasn’t changed much in the last few thousand years? Is it really a “sad commentary on education” that new technologies haven’t transformed schools in the way that books and blackboards have? What if the way the edubas went about teaching ancient Sumerian was, broadly speaking, the best way to go about things? (Obviously, without the beatings!)

Great efforts have been made in the last century or so to ‘revolutionise’ schools. This has gathered pace in recent years because ‘technology has changed everything’. Although this isn’t really true, everything we take for granted as being synonymous with schools is under threat. Various reformers have done away with (or would like to do away with) classrooms, desks, books and even teachers talking to students. Understandably, these efforts have met with some resistance. Why, reformers wonder, are some teachers so resistant to change? This is entirely the wrong question. Teachers, like everyone else, tend to love change, as long as it’s positive. What they (and everyone else) tend to hate is loss.6 Consider a scenario in which a school informs its staff that they are all required to work one less day a week for the same pay. Will anyone resist the change? Teachers complain about ill-conceived ideas about how to run schools and classrooms that add considerably to their workloads. This seems entirely rational.

Where schools are not imposed, they emerge. In the poorest slums and most remote villages of India, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya and China, low cost private schools have sprouted up spontaneously. James Tooley first recorded this phenomenon in the Indian city of Hyderabad which contains over 500 private schools catering to the children of day labourers and rickshaw pullers. These schools even offer free tuition to the children of the poorest and most illiterate members of the communities they serve. People everywhere seem to recognise that where these sorts of institutions don’t exist, or where they are so corrupt they may as well not, adults can gather children in rooms and teach them culturally accumulated wisdom. Obviously, these schools are unlikely to conform to our expectations of what schools in developed nations should look like, but the way in which they operate is essentially the same as the Sumerian eduba. Schools – spaces where children are taught biologically secondary knowledge by adults – have evolved as the simplest, most effective way to handle the business of education.

For what’s it’s worth, I suspect Messrs Plato and Aristotle would be quite startled by modern schools. The fact that what we do today is recognisably similar to what we did in yesteryear is a testament both to the fact that our brains haven’t changed in the intervening time, and that teaching is far simpler than some would like us to believe. So simple, in fact, that some have argued that the ability to teach may well be another biologically primary adaptation.

We’ll pick up the argument about the need for schools in the final post in this series which will examine the role of the teacher.

Andrew R. George, In Search of the é.dub.ba.a: The Ancient Mesopotamian School in Literature and Reality. In Yitzhak Sefati, Pinhas Artzi, Chaim Cohen, Barry L. Eichler and Victor A. Hurowitz, An Experienced Scribe Who Neglects Nothing: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Jacob Klein (Potomac, MD: CDL Press, 2005), pp. 127–137 at p. 127.

Alexandra Kleinerman’s Education in Early 2nd Millennium BC Babylonia: The Sumerian Epistolary Miscellany (2011) offers a detailed examination of the educational practices and social context of scribal schooling in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. Focusing on the Sumerian Epistolary Miscellany—a set of model letters used in scribal education—Kleinerman explores how these texts were employed to teach language, rhetoric, and administrative communication to apprentice scribes. She argues that these model letters served not just a linguistic or literary function, but also played a central role in shaping students’ moral, professional, and social identities. Through analysis of these texts, Kleinerman sheds light on the curriculum, pedagogy, and institutional structures of ancient Mesopotamian education, showing that scribal schooling was as much about cultural indoctrination and social positioning as it was about technical skill development. The study contributes to our understanding of how education functioned as a means of social reproduction in early complex societies.

Egbert of Liège’s The Well-Laden Ship, translated by Robert G. Babcock (2013), is a 10th-century Latin school text that blends moral instruction, Christian teaching, and classical learning into a richly poetic educational manual. Written in verse, the text uses the metaphor of a ship laden with knowledge to explore the purpose and trials of student life, often lamenting the decline of scholarly effort and discipline. Egbert critiques both students and broader society for their diminishing regard for learning, presenting education as a demanding but virtuous voyage requiring perseverance and guidance.

Alvarus Pelagius’s The Plaint of the Church, written in the early 14th century and included in Brian Tierney’s The Middle Ages, Vol. 1: Sources of Medieval History, is a passionate critique of the moral and institutional decline of the medieval Church. Presented as an allegorical lament voiced by the Church itself, the text decries the corruption, greed, and worldliness of the clergy, particularly within the higher ranks. Alvarus—a Franciscan and a canon lawyer—uses the plaint (or complaint) form to express anguish over the Church’s departure from spiritual purity and apostolic ideals. The work reflects broader concerns of the period about the tension between spiritual authority and temporal power, anticipating some of the themes that would later surface in reform movements. It stands as both a moral indictment and a call for reform, illustrating the internal critiques of the Church that emerged well before the Reformation.

Catherine Moriarty’s The Voice of the Middle Ages: In Personal Letters 1100–1500 offers a vivid window into medieval life through authentic correspondence. On page 105, the focus is a letter from a Byzantine teacher to the father of his students, expressing frustration over the boys’ neglect of their studies.

Loss aversion is a well-documented psychological phenomenon where individuals experience losses more intensely than equivalent gains, typically valuing losses about twice as strongly as gains (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). First introduced in Prospect Theory, it explains why people often resist change, overvalue owned items (the endowment effect), and show strong reactions to negative outcomes (Kahneman, Knetsch, & Thaler, 1990). Neuroscience research supports this bias, showing heightened brain activity—particularly in the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex—in response to potential losses (Tom et al., 2007).