We all want progress, but if you’re on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; in that case, the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive.

C. S. Lewis

We tend to believe that things are getting better, that mankind is on a journey to some perfect state in which irrationality will be banished. This belief shapes and distorts our thinking. Darwin’s evolutionary theory of natural selection is often interpreted as meaning that random biological mutations, which are then inherited and selected as being most fit for the context in which a species finds itself, are working towards some ultimate goal. They aren’t. If we accept Darwin’s theory, we also have to accept that our existence is a matter of chance. We are something of a fluke.

Karl Popper, thought something similar was happening in the realm of ideas. He saw the growth of knowledge as being the result of a process closely resembling natural selection. He thought that “our knowledge consists, at every moment, of those hypotheses which have shown their (comparative) fitness by surviving so far in their struggle for existence; a competitive struggle which eliminates those hypotheses which are unfit”.

But even a cursory glance at the history of ideas demonstrates that if this is true, it’s a maddeningly slow process. In education alone many hypotheses which are unfit continue to lurch about our landscape. Maybe we can better understand the spread of ideas by considering Richard Dawkins’ theory of memes and mimetic evolution. In The Selfish Gene, he explains that just as genes are driven to replicate themselves through the process of natural selection, memes – ideas, tunes, images – also replicate themselves in a similarly self-interested way. Through a process of cultural transmission, ideas spread themselves from person to person and from consciousness to consciousness regardless of whether they are good or bad.

Obviously some memes are incredibly useful or beautiful – the ideas of central limit theorem, King Lear, phonetic alphabets, the electric light bulb, the idea of education itself – but others are not. It often seems that all an idea needs in order to be accepted is to be shouted loudly enough and often enough for it to become something we no longer question. When this happens memes enter the realm of conventional wisdom and become self-evidently true in the minds of many; their survival is assured. This is a much better explanation than that there is some sort of conspiracy to hold humanity back from reaching its true potential. Or whatever. As John Maynard Keynes put it, “the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas”.

Our implicit belief in progress hoodwinks us into accepting that results should always be improving and things can only get better. We only have to remember the second law of thermodynamics: everything moves inexorably towards entropy and chaos.1 Any temporary sense of progress is but a beguiling illusion, just another self-interested meme that replicates as it passes from mind to mind.

Back to progress. Is it actually possible for pupils’ learning to improve in a short time or at a great rate and continue for an extended period?

I don’t think it is. Of course we can experience sudden, dramatic breakthroughs but these are rare. Such lightbulb moments are usually the result of the steady accretion of understanding over time – the fact that they seem to happen quickly is misleading. For the most part, you have to make a choice between progress being either rapid or sustained and, this being the case, I’m going to plump for sustained. After all, progress that doesn’t last isn’t really progress, is it? This idea that progress can be rapid has led us into believing that meaningful progress can take place in individual lessons and that learning follows a neat, linear trajectory. Children move from knowing nothing to knowing a little, to knowing a lot in a smooth and easily navigable and safely predictable manner.

This is self-evidently wrong as even a cursory examination of children’s work over time makes clear. Progress is, if anything, halting, frustrating and surprising. Learning is better seen as integrative, transformative, and reconstitutive – the linear metaphor in terms of movement from A to B is unhelpful. The learner doesn’t go anywhere but develops a different relationship with what they know.

Progress, like learning, is an abstraction. My preferred definition for learning is, “the long-term retention of knowledge and the ability to transfer it to new contexts.”2 Retention is concerned with durability, how long things last, whereas transfer is about flexibility, how useable things are in new contexts. We cannot see, in the here and now, whether anything we communicate with be retained or transferred, we can only make inferences from current performances.

Learning takes place inside our minds and as such is invisible, often even to the person experiencing it. All we get to see is performance. Maybe in some dystopian future, students will all be fitted with electrodes and teachers issued with handheld fMRI scanners on which they’ll be able to ‘see’ learning, but until then, we’re stuck with observing students’ performance. Depending on the subject domain being studied a performance might be a dance, an essay, an equation, a recital, an answer to a question or anything else that can be viewed and verified.

From these performances we infer that learning must have occurred. This seems intuitive: if I just showed you how to play the glissado (or smear) at the opening of ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ on your clarinet and now you can perform it for me, you must have learned it, right? Well, maybe. Current performance - especially performance immediately following instruction - is a very unreliable proxy. Maybe you’ll be able to play the piece elsewhere and later, maybe you won’t. In order to know I’d have to follow you around and sample your performance in a range of times and places. That accumulation of performances would be a much more reliable proxy of learning.

As, you can see, once we start interrogating abstract nouns we have to do a lot of work to connect up what we mean with what others might think we mean. In order to ‘see’ abstractions we need metaphor and so, our perception of what ‘learning’ and ‘progress’ means is shaped by the metaphors we use to describe it. I’ve already used the metaphor of an arrow and of an iceberg.3 Both of these shape our understanding in different ways. Importantly, they don’t describe objective reality; they provide a comforting fiction to conceal the absurdity of our lives. We can’t help using metaphors to describe learning because we have no idea what it actually looks like. Even though our metaphors are imprecise approximations, the ones we use matter. They permeate our thinking.

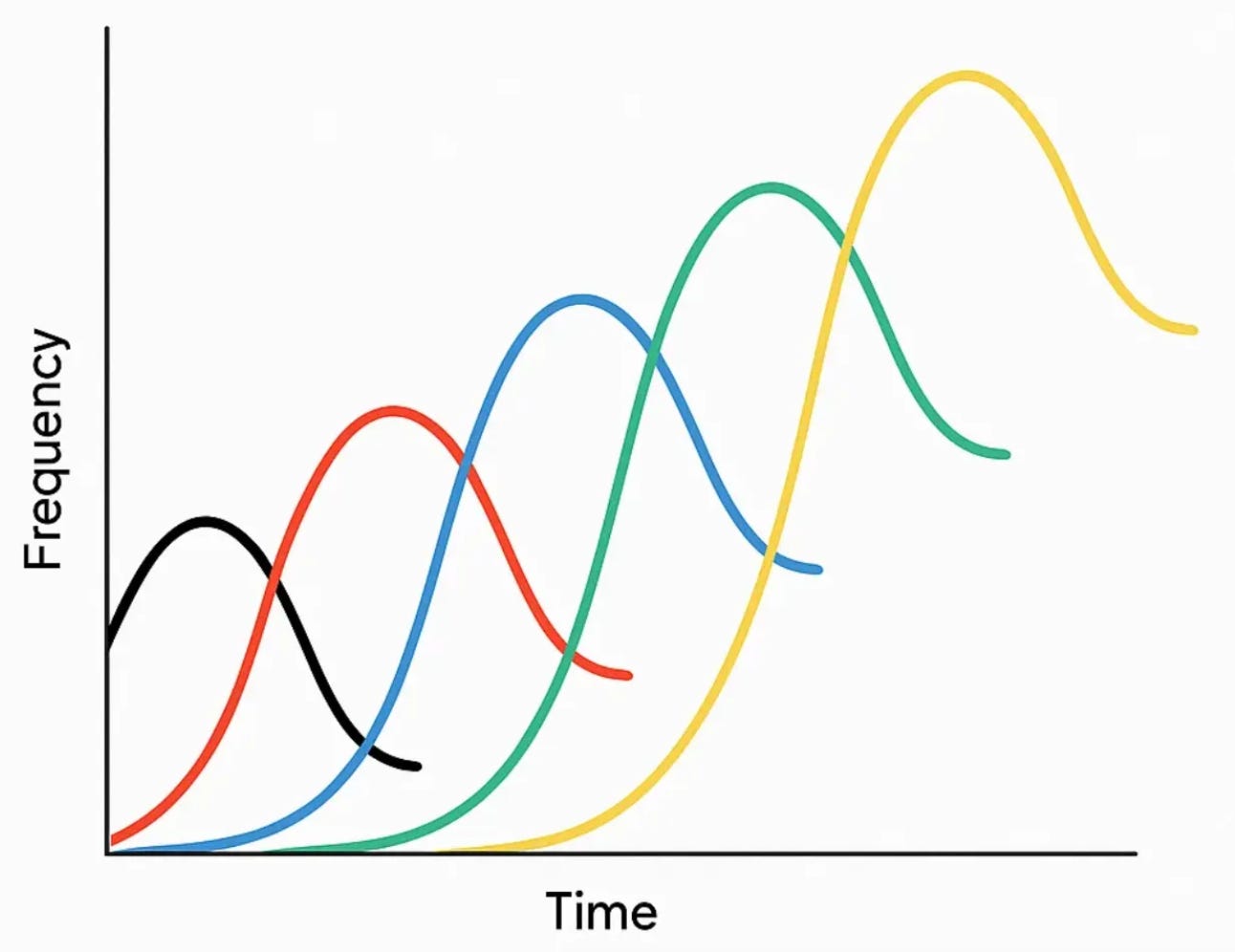

For instance, learning and progress are often conceived as a staircase which pupils steadily ascend. The long shadow cast by developmental psychologist Jean Piaget has meant linear ‘stage theories’ have dominated the way we see the mysterious process of learning. As we know from our own messy journey through life, we often seem to step back or sideways as often as we step up. An alternative metaphor is offered by cognitive psychologist Robert Siegler, who developed the theory that learning is like ‘overlapping waves’.

Piaget saw learning progressing in neat stages like a staircase: children would master level 1 before ascending to level 2, level 3 and so on. Instead, in his book, Emerging Minds, Siegler envisages learning as “a gradual ebbing and flowing of the frequencies of alternative ways of thinking, with new approaches being added and old ones being eliminated as well”. He suggests that as we encounter new rules, strategies, theories, and ways of thinking these wash through our minds like waves, sometimes obliterating what was there before, sometimes pushing suddenly forward in great surges.

This might be a more useful way to frame our thinking about progress. Siegler’s image of surging and receding waves helps to explain the seemingly random retreats and swells we experience as we grapple with new skills and tricky concepts. Rather than feeling ashamed about ‘slipping back’ into the old ways of thinking and acting we thought we had out-grown, such episodes are better viewed as part of the natural ebb and flow of learning. Slipping back is part of the liminal process of integrating new and troublesome concepts into our mental webs of understanding.

If that’s an approximation of what happens ‘in here,’ it’s probably fair to say that something similar goes on ‘out there’ in the world of ideas. No one looking at the geopolitical situation in 2025 would argue (at least, argue convincingly) that it represents progress, but maybe the current ebbs we’re experiencing - like those in the first half of the 20th century - are necessary for some as yet unrealised future paradigm to improve our lives unrecognisably. Maybe.

The entropy of an isolated system not in equilibrium increases because isolated systems always evolve towards thermodynamic equilibrium, a state with maximum entropy.

Or, at a push, “the process of absorbing information and coming to new conclusions.”

Apologies, but the iceberg in the image is an internet fake, an approximation of what we know icebergs should look like. Obviously there’s no way you could take that image as a little critical thinking will make clear.

Your cynicism here is refreshing. But you could trump your own cynicism by stepping back from the metaphor of learning as accumulation/ accretion / addition. It might seem that obvious - that we want stuff to go into head of person - but this too is a metaphor.