The myth of balance in the classroom

Why the case for mixing teacher-led and student-led activities doesn’t stack up

This post was my first paywalled post back in April. Here it is again with the paywall removed.

For as long as I’ve been writing about education, many commentators have argued that teaching should seek to balance teacher-led and student-led activities. Although this is often presented as self-evidently obvious, it rather begs the question. What’s so great about balance? Should we seek balance for its own sake, because it’s intrinsically valuable, or should we consider what we want to balance? Despite balance sounding – well – balanced, no one would argue that we should seek to achieve a balance between effective and ineffective activities, so to argue that teaching should include both teacher-led and student-led activities we really need to make the case that both are inherently worthwhile.

This has been on my mind again because of a recent discussion with a colleague where we explored the idea that teacher-led lessons are more demanding for teachers and that maybe one reason for balancing activities would be allow teachers some down time in lessons where they can catch their breath whilst students get on with something independently. This was an angle I hadn’t considered previously. I’d always taken the view that teacher-led activities (reading aloud, questioning, mediating classroom discussions, using mini whiteboards to ensure participation in thinking and writing and the other activities outlined here) were not only more effective, but also more straightforward for teachers than student-led activities (small group discussions, project work etc.1) Like many teachers, I’ve found the faff involved in trying to make student-led activities work rarely – if ever – repaid the effort. But, as long as the classroom culture for behaviour is good, I can see that most of this effort would be in planning and designing resources to facilitate the activities in advance of, rather than during, lessons.

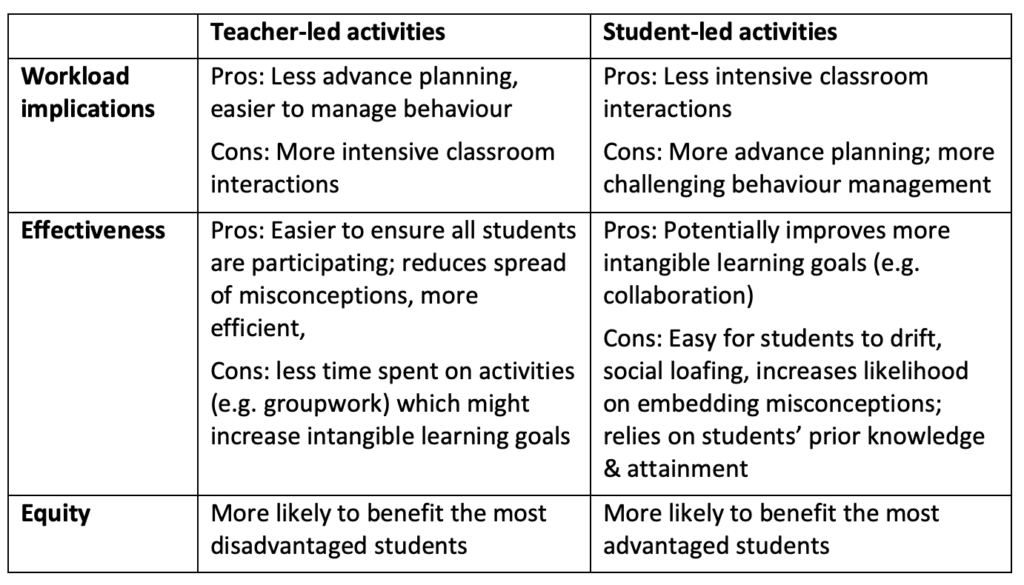

To be clear, I’m not arguing that lessons should never contain such student-led activities (some become more or less important in different subjects and with students of different ages) rather that the balance should be disproportionately in favour of teacher-led activities. To make that argument I think it’s helpful to weigh three different indices: workload, effectiveness and equity.

Workload implications will vary widely and the trade-off seems to be between effort in lessons versus effort before lessons. The effectiveness arguments are well-trammelled and you either accept the evidence or you don’t. In all honesty, I really don’t care that much about whether teachers have their students work in groups or not; what irks me is the idea that teachers should get their students to work in groups.

Those determined to enact student-led learning should be aware of Robert Slavin’s finding that if the purpose of group work is to improve the learning of every member of the group then it will require both group goals and individual accountability. Teachers are generally good at creating group goals but less good at ensuring each member of a group is individually accountable. Selecting a student to report back to the class before the work is finished is a bad error. It means that only one group member is accountable and that everyone else can muck about. If, however, you don’t say who will be reporting until after the task is completed everybody is on their toes. With this sort of tweaking you can do much to ensure that some of the ills of group work are avoided.

But does avoiding negatives mean that students working collaboratively is a good thing? Well, that’s an empirical question. To answer it we need to first agree the aims of teaching. If, as I believe, the purpose of teaching is to expand children’s knowledge base to enable them to think new thoughts then my instinct is that we are best served by interactive whole class instruction. If instead you believe teaching should aim to produce some other, more nebulous aim that results in important but hard-to-see benefits then the onus is on you to say what those benefits are and how we would know whether teaching has an effect.

I’m very sceptical about hard to see benefits and claims such as these:

Student-led learning is incredibly beneficial for both students and teachers. For students, this education style makes learning fun by giving them creative freedom and empowering them to have control over their own learning. It also instils values such as intrinsic motivation, self-discipline, and curiosity. For teachers, it means more time to help students individually and to make sure the class meets long-term goals.

This seems utterly detached from reality. There may be students who find student-led lessons fun, but they’re certainly not a majority with many students hating lessons where teachers are not mediating interactions. Whether such activities instil “intrinsic motivation, self-discipline, and curiosity” is an empirical claim. For it to be accepted you’d need to find a way of measuring increases in such intangibles and then design an experiment to demonstrate it to be true. So far, this threshold is yet to be met. The final claim, that teachers will be rewarded with more time to help students, not only depends entirely on the extent to which students behave appropriately but should also be weighed against the probability that teachers will need to spend more time unpicking mistakes and misconceptions caused by student-led activities. The claim that having more student-led learning will help teachers “make sure the class meets long-term goals” seems both impossible to prove and highly implausible.

What does the evidence tell us?

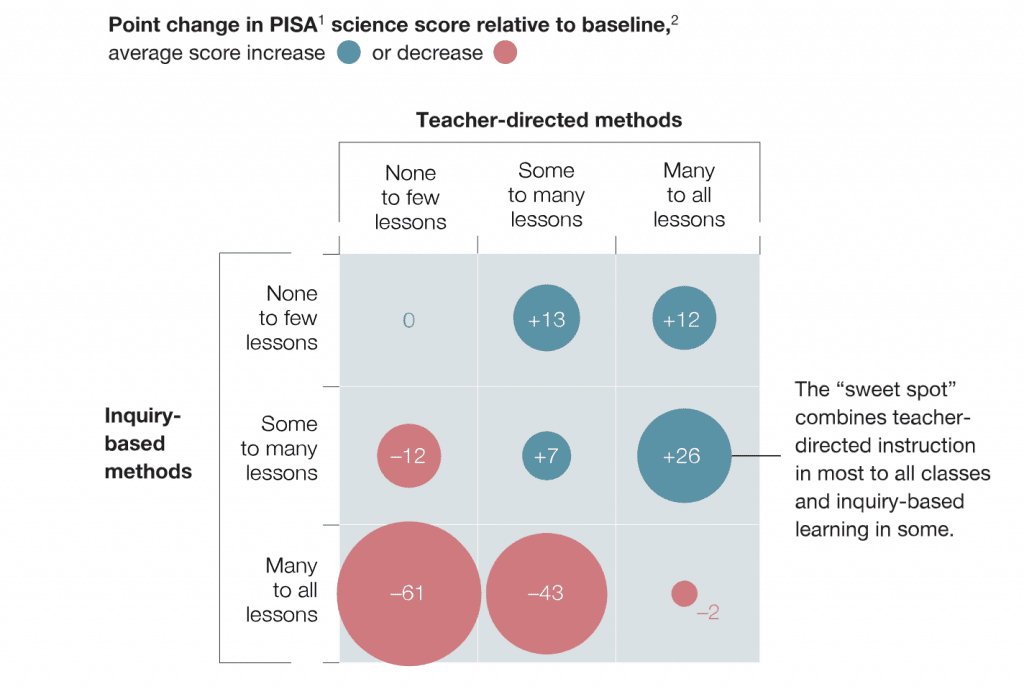

The 2015 PISA results provide a useful data source. According to students’ self reports, teaching is far more likely to be teacher directed than to involve enquiry-based methods (into which category I would place group work and collaborative learning). Even in systems which report far less teacher direction, the ratio is still about 2:1 and in some territories the ratio is closer to 4:1. In the highest performing systems the ratio is about 3:1. McKinsey’s analysis suggests this is the sweet spot and the best approach “combines teacher directed instruction is most to all classes and inquiry based learning in some.”

The more lessons focus on inquiry-based methods the lower student attainment becomes. These findings are also born out by a variety of other sources. Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction (Begin a lesson with a short review of previous learning; present new material in small steps with student practice after each step; ask a large number of questions and check the responses of all students; provide models; guide student practice; check for student understanding; obtain a high success rate; provide scaffolds for difficult tasks; require and monitor independent practice; engage students in weekly and monthly review.) are all hallmarks of fully guided instruction and largely absent from most iterations of collaborative learning. As Rosenshine points out, his principles are derived from “three different sources: research on how the mind acquires and uses information, the instructional procedures that are used by the most successful teachers, and the procedures invented by researchers to help students learn difficult tasks.” He goes on:

Even though these principles come from three different sources, the instructional procedures that are taken from one source do not conflict with the instructional procedures that are taken from another source. Instead, the ideas from each of the sources overlap and add to each other. This overlap gives us faith that we are developing a valid and research-based understanding of the art of teaching.

Putting Students on the Path to Learning, as article by Richard Clarke, Paul Kirschner and John Sweller provides yet more support for fully guided instruction. Their position can be summarised as follows:

Research has provided overwhelming evidence that, for everyone except experts, partial guidance during instruction is significantly less effective than full instruction.

I’m very sceptical about hard to see benefits and claims such as these:

Student-led learning is incredibly beneficial for both students and teachers. For students, this education style makes learning fun by giving them creative freedom and empowering them to have control over their own learning. It also instils values such as intrinsic motivation, self-discipline, and curiosity. For teachers, it means more time to help students individually and to make sure the class meets long-term goals.

Added to this we also have the incredible success of Engelmann’s Direction Instruction model. DI is a very specific method of both teaching and curriculum design. It takes as its starting premise that if children struggle to learn, this should be seen as a problem with the instructional design rather than evidence that the child is incapable of learning. Engelmann sought to eliminate anything in his instructional sequences that could be considered ambiguous or misleading with the result that his scripted programmes could be faithfully reproduced by any teacher anywhere.

Project Follow Through, the largest, most expensive education study ever conducted involving over 70,000 students in 180 schools across the US ran from 1967-1995. Follow Through pitted various approaches to teaching against each other in a straight horse race with Direct Instruction the clear winner in all categories. Not only was it the most effective programme at improving students’ literacy and maths skills, it also outperformed all other models for more generic cognitive skills and other affective areas such as self-esteem and student engagement.

As we all know, Direct Instruction did not go on to conquer the world as the most effective method for teaching children. In fact, as Douglas Carnine observed:

[DI] was not specially promoted or encouraged in any way…federal dollars were directed toward less effective models in an effort to improve their results…. [S]chools that attempted to use DI —particularly in the early grades, when DI is especially effective—were…discouraged by education organizations.

The fact that few teachers are even aware of what DI actually is, let alone use it in the classroom speaks volumes. Despite this, teacher-directed instruction seems to be far more common than student centred approaches. I reckon the reason most teachers gravitate towards whole class teaching is that it’s easier. Getting group work right is hard. Just telling kids things is usually whole lot simpler than expecting them to work together to find them out.

But, is it equitable?

However, I think the most important of these lenses in my matrix above is the final one, equity. My argument here is that the more socially advantaged and the higher prior attaining a student is, the more likely they are to benefit from being time to discuss ideas and engage in independent work. At worst, they are less likely to be negatively affected and are often successful despite engaging in student-led activities. But for students who are less socially advantaged, lower attaining, diagnosed with SEND or marginalised in any other way, the more likely these students are to benefit from teacher-led activities where fewer assumptions are made about prior knowledge and cultural or social capacity. In fact, I’d go so far as to suggest that these students are only likely to be successful if given a classroom diet of mainly teacher-led activities. All children are likely to benefit from teacher-led activities, but disadvantaged children will benefit disproportionately.

This, I think, is the crux of the matter: student-led activities are, albeit inadvertently, gap widening, whereas teacher-led approaches are more likely to be gap narrowing. When trying to determine the correct balance between different approaches it’s very easy to say that lessons should balance teacher-led and student-led activities but much harder to argue that lessons should balance gap narrowing and gap widening activities.

The ultimate aim is – of course – that students are independent, but (as I argued back in 2013) teacher-led activities are the most reliable mechanism for getting them to that point.

Now, you might want to take issue with any, or all, of the conclusions above but I still think this enables us to weigh up the potential costs and benefits to choosing teacher or student-led classroom activities. My key question is this: if you’re going to include student-led activities, how will ensure they don’t end up widening the advantage gap?

The caricaturing of explicit instruction

As you can see in the infographic below, there are certainly many alternative takes that caricature the idea of teacher-led activities and make up lots of nonsense about the supposed virtues of student-led approaches.

Honestly, I’d argue the opposite to be true for most of these categories. My approach to teacher-led lessons definitely designs the classroom around students’ needs, with fast-paced interaction, failure always recognised as “teachable moments” and centred on the belief that all students can be successful if instruction is gapless. It’s particularly ironic that the student-led side of the graphic above includes the caption “Teachers lead, coach and inspire learners.” Of course teachers should be responsible for meeting students’ needs (the alternative is to not take responsibility which is, er, irresponsible), of course classrooms should be controlled (again, the alternative is to be out of control!) and of course teachers should focus on teaching subject content (what would happen to disadvantaged students if they didn’t?)

I’m happy to accept the definition of student-led activities offered by this website (although I’m obviously not prepared to accept the benefits it claims.)

I agree with you about this. I've only been teaching for two years (United States), and based on anecdotal evidence and my gauge of how my students feel: they like the lessons that are teacher-led, highly structured, and guided/direct.

I was always wary of "student-led" instruction. What disturbed me during my training was when my mentor said, "teaching is just facilitating now. Give them the work and give yourself a rest". I suspect sometimes that this leaning towards "student-led" instruction is because of teacher burnout. But teaching lessons, if they are well-designed, can actually be incredibly energizing.

The idea that students will take initiative and take ownership of their learning experience is a pipe dream. Where I teach, only certain college-level courses with high performing students can even try to approach that ideal. From how I see it, my students are really refreshed when they see me actively involved in all parts of the lesson. They're sick of the onus being put on them.

Thank you for compiling and summarizing all that research!

Thank you for this article. I enjoyed reading it.

I agree with many of the statements made, after nearly three decades of teaching experience.

For me, the focus is always on the student, the protagonist of learning. But the teacher's role is necessary in teaching, and they need to have the courage to want to teach, even if that idea doesn't sound good to some.

We need to cultivate—in my opinion—a new vision of the need for transmission, along with the constant study that it demands of the teacher.

I think we often face a situation that is more rhetorical than educational, which requires a rethinking of teaching from the perspective of the various agents and essential elements of the educational process, viewed from the perspective of purpose.

We can intuit what it means to be a good citizen, but we need to learn and want to be one. My proposal is to foster social attitudes such as optimistic altruism, responsibility—both social and political—respect, loyalty, and justice, all supported by personal freedom.

The role that teachers play in this area, as described here in terms of equity, is truly important.