As a semi-regular feature, I’m planning to pick out some of my favourite academic papers and say what I love about them and why I think they should be read. This is the first.

In 1956, the clinical psychologist Paul Meehl published a quiet bombshell of a paper: Wanted – A Good Cookbook. At face value, it was a critique of how clinical psychologists made predictions. But read carefully, it was also a philosophical intervention, one that challenged the very idea of professional judgment, and demanded that experts of all kinds take their epistemic responsibilities seriously.

Meehl’s central concern was not that professionals were dishonest or malicious. It was that they were confident, sincere, and wrong. Long before the rise of behavioural economics or the formal study of cognitive biases and heuristics, Meehl was already diagnosing the unreliability of expert intuition, the dangers of overconfidence, and the human tendency to see patterns where none exist. His work anticipated, by decades, the empirical findings that would later become central to the fields of decision science and psychology.

His argument was a practical expression of what philosophers from Socrates to Popper have insisted for centuries: good intentions do not guarantee sound knowledge. As Samuel Johnson pithily put it: “Hell is paved with good intentions.” And in fields like psychology or education, where decisions affect real lives, epistemological sloppiness does not just result in technical errors but in moral failure.

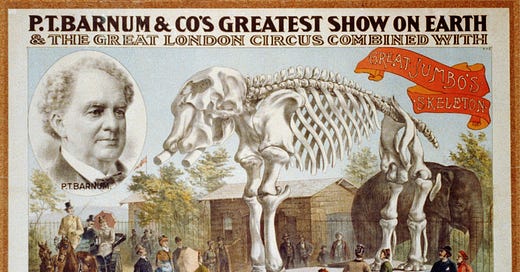

Meehl was among the first to identify what would later be termed the Barnum effect: our tendency to accept vague, broadly worded statements as if they were uniquely descriptive of us. These are assertions that carry the illusion of precision while offering no real specificity. They sound insightful but reveal nothing.

In psychology, such statements often appear in assessment reports and clinical interviews. Phrases like “You are capable, but tend to underestimate yourself” or “You struggle when you feel unsupported” seem to capture something personal. Others strike a familiar chord: “You value independence, yet seek the approval of others.” But these observations, however polished, are so broadly applicable that they could describe almost anyone. Their plausibility is precisely their danger; they create the appearance of understanding without offering anything that can be tested, questioned, or falsified. As Meehl put it, “Statements which are true of practically all human beings are commonly accepted as uniquely descriptive of the individual case.”

Meehl was careful to note that clinicians did not use these formulations out of laziness or bad faith. On the contrary, many believed they were offering meaningful insights. The problem was subtler and more pernicious: when a statement can apply to anyone, it cannot reliably diagnose anyone. Its resonance makes it feel true, but that resonance is what renders it epistemically empty.

Meehl’s paper exposed a hard truth: expert intuition - no matter how confident or compassionate - is often no better than chance when it is not tethered to a structured method. In effect, he was warning against the misuse of intuition in what Robin Hogarth would later describe as ‘wicked domains’ (environments like clinical psychology or education, where feedback is inconsistent, outcomes are delayed, and meaningful patterns are difficult to detect.) Unlike ‘kind’ learning environments (where experience sharpens judgment through clear, immediate feedback) wicked domains offer little correction. They allow confident error to pass unchecked, after all, “The clinician may think he sees what isn’t there, and may think he knows what he doesn’t know.”

Meehl grasped this long before the terminology existed. He understood that in these settings, experience can reinforce illusion just as easily as it can build insight. We come to believe things will happen based on past patterns, but we can never know with certainty that they must. Belief arises from habit, not from logical necessity.

This echoes David Hume’s deeper insight: that belief, however sincere or familiar, does not amount to knowledge. As Hume wrote, “custom, then, is the great guide of human life,” but custom cannot guarantee truth. Hume’s point is that belief, even widespread, deeply felt belief, is not the same as knowledge. Although we form beliefs through habit, this offers no guarantee of their truth or logical soundness.

This is a classic Humean example: we believe in gravity not because we deduce it from reason, but because we have observed it consistently. The sun rises, apples fall, objects drop when released so we assume they always will. Yet we cannot prove that gravity must operate tomorrow as it does today. Our certainty rests on custom, not necessity.

The same kind of habitual beliefs are omnipresent in education. Teachers and leaders often rely on assumptions formed through repeated experience, but these assumptions - however familiar - are not logically guaranteed. For instance, quiet students are often assumed to be well-behaved, even though silence can just as easily mask disengagement or confusion. Hard work is commonly believed to lead to success, though countless structural and contextual factors complicate that trajectory. Similarly, more experienced teachers might typically be seen as more effective, a belief supported by patterns but far from universally true. In each case, the belief feels right because it is familiar, not because it is necessarily reliable.

These kinds of habitual, experience-shaped beliefs are not limited to theories of gravity or causal inference—they play out, quietly and persistently, in the everyday fabric of professional life. The Barnum effect manifests in countless subtle ways: a teacher might be described as “outstanding” after delivering one high-energy lesson during an observation, the judgment grounded more in charisma than in any sustained evidence of impact. A student is labelled “resilient” for remaining calm in a single challenging moment, despite no clear pattern of coping across time. A classroom is deemed “highly engaging” because the atmosphere is upbeat, even when substantive learning is difficult to detect. These judgments feel plausible -generous, even - but they rest on surface impressions rather than structured, testable insight. They are acts of epistemic overreach: confusing warmth for rigour, familiarity for evidence, and plausibility for truth. And just as easily, the inverse occurs, less flattering, even career-damaging judgments are made with the same casual confidence and lack of constraint.

Such judgments are rarely made with malice. They emerge from habits of mind; professional instincts shaped by repetition, routine, and plausibility. But when those instincts go untested, they drift into illusion. This is precisely the danger Meehl saw. It wasn’t that he was cynical about experts, he was realistic about the limits of human judgement. Without structure, our judgement becomes unreliable no matter how well-intentioned. Left to intuition alone, we are all prone to conflate vibes with veracity.

Why a cookbook?

The phrase “cookbook psychology” was originally an insult, implying that using structured procedures was simplistic or mechanical. Meehl flipped the metaphor on its head: “A good cookbook is better than a poor intuition.” If clinicians - or teachers, or policymakers - make judgments that are inconsistent, untested, and unreliable, then surely a good cookbook is a moral upgrade. Meehl argued that by exposing error and reducing bias, constraints enable wisdom.

The same structural problems are deeply embedded in educational systems. A pastoral log might record “improved effort” based on nothing more than eye contact and body language during a single interaction, rather than any sustained pattern of work. Behaviour records often blur the line between fact and interpretation, mixing concrete incidents with subjective judgments like “defiant tone” or “poor attitude.” Even teacher appraisal systems frequently reward charisma, humour, or decorative classrooms while overlooking the substance of what is actually taught or learned. These patterns persist not because teachers lack skill or care, but because the system often lacks the structures needed to distinguish appearance from evidence.

These problems do not arise from bad intentions, but from the absence of systems that guide and constrain judgment, systems that make our inferences more honest precisely because they make them accountable.

To borrow from Popper, “A theory which is not refutable by any conceivable event is non-scientific.” That principle - falsifiability - holds that a claim must be open to disproof through evidence if it is to count as serious knowledge. If no possible observation could show a judgment to be wrong, then it is not a meaningful claim, it is an opinion dressed as insight. Meehl’s work made this idea concrete. If your professional judgments cannot be tested, questioned, or contradicted by evidence, they are, to all intents and purposes, bullshit.

Four lessons from Meehl’s Cookbook

Fallibility is a feature of human thought, not a flaw. To trust ourselves less is to be more professional

Vagueness is the enemy of moral clarity. If a judgment cannot guide specific action, it cannot justify its consequences

A structured method is a form of intellectual humility. It says: I know my mind is biased, so I will build in checks

Professionals carry epistemic responsibility. When others act on your judgment, you owe them more than confidence.

Meehl’s essay remains urgently relevant for anyone whose professional authority depends on making judgments about people, especially in education, where young people must live with the consequences of adult decisions. In such contexts, we are called to exercise not just care, but clarity. As Hannah Arendt observed, “The greatest evil… is committed by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.” For Arendt, thoughtlessness - the uncritical acceptance of roles, routines, and language that obscures moral responsibility - was more corrosive than malice. Meehl’s work, like Arendt’s, exposes the danger of professionals acting without reflective scrutiny, of saying things that sound meaningful but rest on vague impressions rather than evidence.

Where Arendt warned of the ethical vacuum in bureaucratic obedience, Meehl offered a psychological diagnosis: without structures that constrain and test our judgments, sincere professionals are likely to make claims that cannot be defended and that may do real harm. As Thomas Sowell said, “It is so easy to be wrong – and to persist in being wrong – when the costs of being wrong are paid by others.” To think - and act - with care is the essence of moral accountability.

Meehl’s call was simple: we need a ‘cookbook’ not because we should respect the lives professional judgement affects too much to let vague confidence stand unchallenged. In education, where judgments shape opportunities, reputations, and futures, the margin for error is not abstract. When we describe effort, character, or quality without clear evidence or shared definitions, we risk building systems that reward style over substance and intuition over understanding.

That’s why I love this paper. It is a call for professional scepticism. Meehl never sneers or caricatures; he calmly insists that professionals have a duty to think clearly, test their assumptions, and resist the comforting pull of vague insight. His challenge still stands: if our work involves making decisions about people, then our thinking must be disciplined, testable, and accountable.

Have you any suggestions of papers that have had an impact on you? What do you think I ought to read? Recommendations are welcome.

Your points around the Barnum effect seem to closely mirror things we regularly see on SEND Pupil Passports and the like. How can we avoid this pitfall, when these are regularly written by low-paid teaching assistants, who may have neither the time, the inclination or the capacity to tailor them further? I fully agree that they're meaningless, FWIW.

Do charisma, humour and colour automatically prelude rigour? I've always found this idea a bit daft. If one is rigorous about the presentation of one's alleged charisma, if one is pointed and determined in rigorous use of humour, if one displays student work as exemplars of what we're going for, isn't it more than likely we'll also be rigorous about content? A very good piece of wiring, as ever, I may even read the original paper.