Stop misjudging people: the hard truth about how bias works

How the Fundamental Attribution Error makes fools of us all

When I posted this on Saturday morning something a bit odd happened and it wasn’t emailed out to most subscribers. I’m publishing it again today in the hope that a few more people will get to see it.

If you were one of the few who where emailed this yesterday, apologies and please feel free to delete.

Thanks, David

The error lies in our inclination to attribute people’s behavior to the way they are rather than to the situation they are in.

Chip Heath, Switch

In education - as in life - we are rarely short of strongly held opinions. Every initiative, policy tweak, or behavioural fad attracts a chorus of knowing nods and righteous fury. The debates are lively. The positions entrenched. And yet, so much of this noisy back-and-forth rests on a common and rather silly cognitive trap: the Fundamental Attribution Error.

The Fundamental Attribution Error, or FAE, isn’t new. The term was coined in 1977 by social psychologist Lee Ross, though the habit itself predates the label by several millennia. At its core, the FAE is our unfortunate tendency to explain other people’s behaviour by appealing to their personal qualities, while explaining our own behaviour by appealing to our circumstances. Ross explores how ordinary people try to understand and explain the behaviour of others, acting as “intuitive psychologists.” He argues that while people are skilled at generating explanations for behaviour, they are also systematically prone to predictable errors. He said, we have “a pervasive tendency to see behaviour as a reflection of stable personal traits even when it can be fully explained by situational factors.”1

If someone cuts you up on the motorway, your first thought isn’t usually that they’re having a rough day or were momentarily distracted. No, they’re a selfish, reckless, inconsiderate idiot who shouldn’t be allowed behind the wheel. But if you cut someone up, well, that’s different. You didn’t see them, or you had to swerve to avoid another car, or you were rushing to make a hospital appointment. Your mistake was circumstantial; theirs reveals their character. If a colleague struggles with a class, we might sigh and think: weak behaviour management, poor subject knowledge, lack of resilience. If we struggle with the same class, it’s because we’ve been given the bottom set again, the timetable is a disaster, and the curriculum was rewritten over half term.

The problem is perceptual: we see people behaving badly or foolishly, but we rarely see the situational factors pressing on them. As philosopher Albert Michotte pointed out, we can never see causes; we only see effects. In The Perception of Causality, he explored how people instinctively impose causal interpretations on what they observe, even when no genuine cause is visible. Michotte demonstrated that we are hardwired to see one event as the cause of another - for example, when one object appears to ‘launch’ another - even though all we actually perceive are sequences of movement. We don’t witness causality; we invent it. This is precisely what happens when we judge others: we see behaviour and instinctively weave a story of personal traits as its cause, while the invisible situational factors are quietly erased.

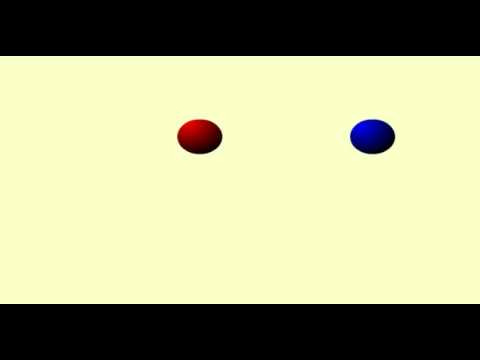

When an animation shows a red ball moving swiftly towards a blue ball, we tend to ‘see’ the red ball collide with the blue and impel it across the screen. The faster the movement, the stronger this perception of causality. But slow the animation down, and the illusion fades: we no longer think the red ball’s movement as causing the blue ball’s. All that’s changed is speed, but our minds leap from sequence to cause. Just as with people, we don’t witness causality, we invent it. We see behaviour, and we fill in the gaps with stories that flatter our biases and hide the messy reality of context.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to David Didau: The Learning Spy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.