What is assessment for?

Professor Rob Coe argues that for assessment data to be useful it must meet five criteria. Assessments must be:

Informative – they must tell you something you don’t already know and have the potential to surprise

Accurate – we must be able to weigh the trustworthiness and precision of the data produced

Independent – if there is an expectation that students should achieve at a particular grade or level this will distort any data produced

Generalisable – we should be able to make useful inferences about what students are likely to achieve in other circumstances

Replicable – if data would be different at a different time or place then it tells us little of any use.

If any of these criteria cannot be applied to the data produced by an assessment then, Coe argues, it was not an assessment.

The word assessment comes from the Latin for ‘sitting alongside’ (the same root as assistant). This suggests that assessment should assist us in our teaching. Thinking in this way should lead us to ask, how can we use assessment to help us to make better decisions to improve our teaching and students’ learning?

Typically, we think about assessment as an event, a thing that happens periodically. Students sit some form of test which teacher have to then mark, before inputting numbers into a spreadsheet, usually for benefit of someone else. Needless to say, this is an unhelpful view.

Instead, we should view assessment as a process of collecting evidence – sampling students’ retention and application of the things we have taught – using it to make inferences about what students know and can do, then acting on those inferences in the classroom. To be effective, teaching – and curriculum – should be driven by the information gathered in this way.

Every lesson is an opportunity to establish whether students are mastering the content of the curriculum and then responding to what is established.

Teaching and assessment are – or should be – inextricably linked. Unless sequences of instruction include regular checking for retention, understanding and application they are unlikely to be effective. Or, more accurately, we’ll have no way of establishing whether they are effective.

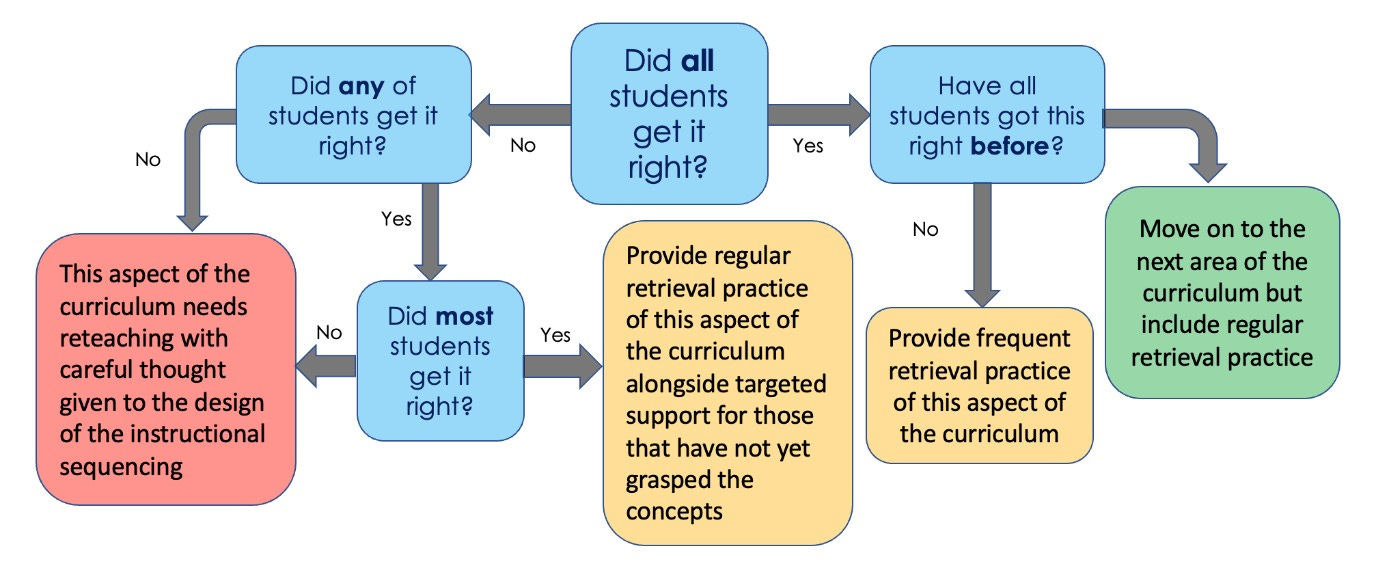

The flowchart above is an attempt to illustrate what might happen in response to students’ performance. My hope that this is this is both simple enough and broad enough to be applied to any assessment.

The starting point whenever students have been asked a question or set a task is to ask whether all of them performed as expected. If the answer is no, we then need to ask whether any students managed to perform as expected. If most students are unable to meet our expectations, then we ought to assume the fault is with either our teaching or the curriculum. It’s become popular to state that we should ‘obtain a high success rate,’ but what does this mean? According to Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction, “it was found that 82 percent of students’ answers were correct in the classrooms of the most successful teachers, but the least successful teachers had a success rate of only 73 percent.” Rosenshine suggests that, “A success rate of 80 percent shows that students are learning the material, and it also shows that the students are challenged.” It’s important to note that this 80% rule is applied to an individual student’s score, not the percentage of students in a given class. For clarity, I would rephrase this as, a success rate of 100 percent of students achieving at least 80 percent shows that they are learning the material and appropriately challenged.

However, we need to think seriously about what we mean by challenge. Should we deliberately ask questions we think most – or some – students will be unable to answer? If students are unable to answer questions, it should be assumed that where there are gaps in student performance there will almost certainly be gaps in instruction. If it were possible to specify and teach a curriculum perfectly, all students would get close to 100%.1 Realistically, we’ll never come near this state of perfection, but we should expect performance to be as high as possible and that if students fail to meet a threshold of confidence the assumption should be that there is a fault either with the design of the curriculum or in its teaching. If we follow Rosenshine’s advice, any students scoring lower than 80% should be cause for concern.

If more than 1 or 2 students are struggling it makes sense to go back to the drawing board, think carefully about whether any gaps have been left in the instructional sequence and reteach with new explanations and examples. All students – even those who have already been successful – will benefit from additional practice. If all students are successful, we next need to ask whether this is the first time. If it is, we should be cautiously pleased but assume that lots of additional practice will be necessary. If it isn’t, we should move on but remain mindful that students will inevitably forget over time and plan to return to this area in the not-too-distant future.

Wherever possible, it’s important to have subject level discussions with colleagues teaching the same curriculum to see if they are experiencing similar difficulties or have useful advice to offer. If it’s a curriculum you haven’t planned yourself, it’s probably worth speaking to whoever designed it to get a sense of whether their expectations match yours.

Just because we’re thinking of assessment as a continuous process and an essential part of the act of teaching doesn’t mean that students shouldn’t also experience periodic assessment events. How we design the tests students sit is of crucial importance if we are going to take our 80% confidence threshold seriously. With this in mind, we need to know how to design and administer mastery assessments.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to David Didau: The Learning Spy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.