Overconfident by design

How confidence distorts judgement, drives action and fuels learning

Overconfidence has an impressive roll call of victims. Notoriously, the builders of the Titanic were so certain of their ship’s invincibility that lifeboats were an afterthought. We all know how that ended. In 1961, US strategists convinced themselves that a small force of Cuban exiles could topple Castro. The Bay of Pigs Invasion collapsed in days. Two decades later, NASA launched the Space Shuttle Challenger despite engineers’ warnings, trusting managerial optimism over awkward doubt. The disastrous launch which resulted in the death of all crew members, was broadcast live on television. More recently, the financial crisis offered its own morality tale, as banks priced risk models with exquisite certainty until reality intervened. It wasn’t ignorance that brought down Lehman Brothers but misplaced faith in what its leaders believed they understood.

These stories have hardened into parables. Overconfidence is cast as the villain of human judgement, the psychological flaw that turns clever folk into fools. We trot out truisms about cognitive biases, hubris, and the comforting belief that if only decision makers were more modest, more humble, catastrophe could be averted. This is an attractive, flattering story. We would not have made those mistakes. We know better. Of course we do.

Our overconfidence in our own belief that we would not fall victim to overconfidence is, or should be, an alarm call. It is well established that around ninety percent of people believe they are better than the average driver. The same logically impossible pattern turns up wherever self judgement is invited. Most managers rate themselves as above average. Most academics believe their work is more rigorous than their peers’. Most people think they are less biased than everyone else.1

Everywhere humans act under uncertainty, overconfidence follows. But why should this be? If overconfidence were only destructive, natural selection would surely have dealt with it long ago. The more interesting question is not why confidence sometimes leads to disaster, but how it so often galvanises us to act.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

We are well practised at rehearsing the dangers of overconfidence. David Dunning and Justin Kruger have become bywords for the uncomfortable but satisfying finding that those who know least are often the most certain. Their work is routinely invoked as a cautionary tale about the hazards of ignorance combined with confidence.

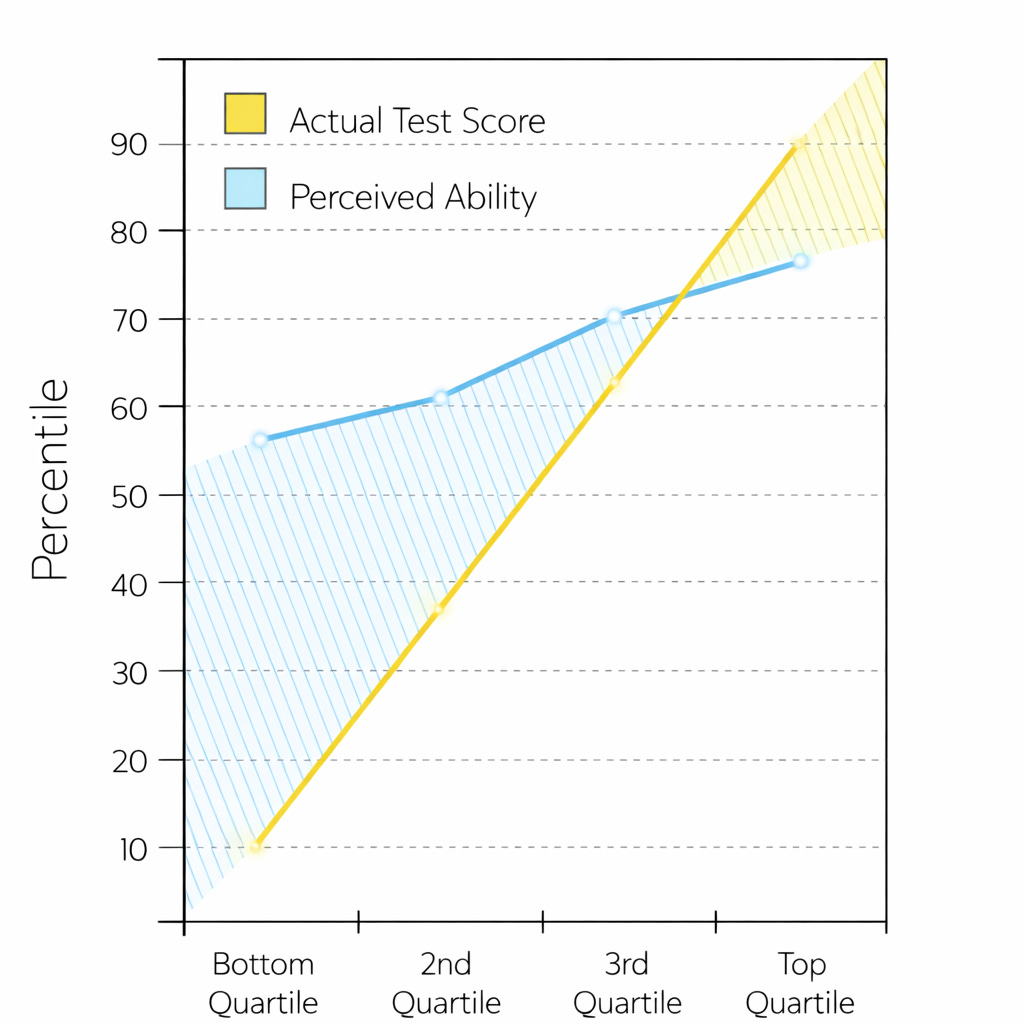

In their original studies, people who performed worst on tests of grammar, logical reasoning, and humour were also the most likely to rate their performance as above average. Those in the bottom quartile not only made the most mistakes, they appeared largely unaware that they were doing so. Lacking the knowledge required to produce correct answers, they also lacked the knowledge required to recognise incorrect ones. The same deficit does double duty.2

High performers showed the opposite pattern. They tended to underestimate their relative standing, assuming that tasks they found straightforward must also be straightforward for others. Competence bred a kind of misplaced modesty. The result was a neat and unsettling symmetry. The least skilled were confidently wrong. The most skilled were cautiously right. This is the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

The effect has proved pervasive across domains. People overestimated their ability to drive, to manage money, to judge risk, and to assess their own expertise. Training reduced the gap, but not by making everyone more confident. Instead, instruction tended to puncture the confidence of the weakest performers while sharpening the calibration of the strongest. Learning did not simply add knowledge. It changed how people judged what they knew.

These findings are often summarised as a joke about fools and arrogance, but the joke misses what’s actually going on. Later work by Dunning and Kruger substantially refined their original claim. Poor performers were not especially vain or foolish, rather, they lacked knowledge about the standards by which performance should be judged. Crucially, when their skill improved, self insight improved with it. Training tended to reduce the confidence of the weakest performers while sharpening the calibration of the strongest. High performers, meanwhile, often underestimated their relative standing, assuming that tasks they found easy must be easy for others. The size and persistence of the effect varied by domain, shrinking where feedback was clear and immediate and persisting where outcomes were noisy or delayed. Overconfidence, it turns out, isn’t a fixed character trait but a context dependent symptom of missing knowledge.

Kind & wicked domains

When we do not know what good performance looks like, we have no reliable way of measuring our own. Confidence, in these cases, is a guess dressed up as certainty. This is not just a novice problem. Studies of medical expertise show that experienced radiologists often become faster and more confident in their judgements without becoming more accurate at detecting subtle cancers. Experience improves fluency and decisiveness, but accuracy can plateau while confidence continues to rise.3

The implication is uncomfortable. Feeling sure is a poor proxy for being right, even among experts. Confidence is far better correlated with familiarity than it is correctness. Where standards are opaque and feedback is delayed or ambiguous, certainty grows in the absence of calibration.

Robin Hogarth’s distinction between kind and wicked learning environments helps explain why confidence is so often untethered from accuracy. In kind domains, feedback is frequent, timely, and unambiguous. Actions lead to clear outcomes and errors are hard to ignore. Chess, arithmetic, and many sports fall into this category. Practice steadily improves performance and confidence becomes better calibrated because reality keeps correcting it. Meteorology is a good example: if you predict rain, you get clear, unambiguous feedback on whether your prediction was correct. Meteorologists quickly learn the difference between signals and noise and thier expertise is refined through experience.

Wicked domains are different. Feedback is delayed, noisy, or incomplete. Outcomes depend on many interacting factors and it is rarely obvious which judgement caused which result. Wicked domains include politics, investing, senior management, and much of professional decision making sit firmly here. In these environments, experience increases familiarity and fluency, but offers little reliable information about error. Confidence is free to grow because mistakes can be rationalised, attributed to bad luck, or simply never discovered. Hogarth’s point is not that intuition is useless, but that intuition is educated by the environment that trains it.

In kind environments, confidence is a useful signal because it is grounded in repeated correction. You feel confident because past judgements of that kind have usually been right, and you have been shown when they were not. In wicked environments, the link between judgement and outcome is broken. You do not reliably find out whether you were right, or why. Errors are delayed, masked, or confounded by other factors. In those conditions, confidence cannot be trained by reality. It grows instead from familiarity, narrative coherence, professional status, or sheer repetition. The feeling of certainty reflects how fluent the judgement feels, not how accurate it is.

Heuristics and biases

Human judgement is stitched together from mental shortcuts that work tolerably well most of the time but betray us at the margins. This way of thinking owes much to the work of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, who set out to understand how people make judgements under uncertainty when calculation is impossible and time is short.