It's Your Time You're Wasting: Uniform Thinking

Are school uniform rules more about equality or control?

Once again, Martin Robinson and I bring you another episode of our much loved (at least by us) education discussion show, this time on the possibilities and pitfalls of school uniform.

Here’s is a link to the audio only podcast. And, as ever, the write up of our discussion continues below.

Here in the UK we have an obsession with uniforms. From ‘bobbies on the beat’ to barristers in horsehair wigs, we love a bit of professional cosplay, but nowhere is this fetish more pronounced than in our schools.

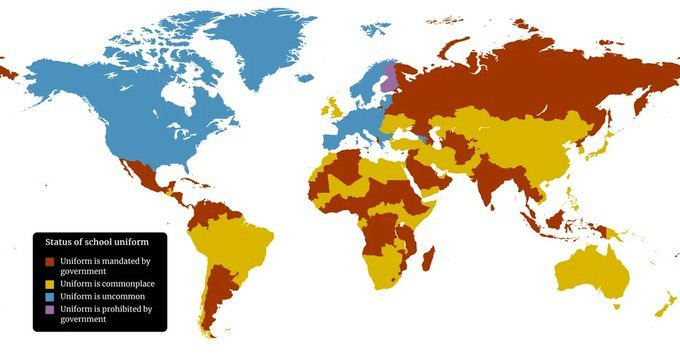

Compared to most countries, the UK is something of an outlier in the what’s referred to as the ‘West,' although as this map indicates, school uniforms are common in most parts of the world.

While only about 20% of American public schools enforce uniforms, in England, it’s closer to 90%, rising to 99% in secondary schools. Why? Tradition, mainly. The idea of school uniform stems from Tudor charity schools, like Christ’s Hospital (founded 1552), which dressed pauper children in blue coats to signify piety and humility. Victorian public schools turned it into a class signal, a way to breed conformity, obedience, and the right kind of young gentleman.

Over time, uniforms trickled down the system, merging old-fashioned discipline with modern branding. Today, they’re less about forming moral character and more about forming corporate identity. Your school is a product, your blazer is the logo.

So what do uniforms actually do and who do they really serve?

The case for uniforms (Or: “We’re all equal in polyester”)

On paper, uniforms are egalitarian. Everyone wears the same thing, so social differences melt away. No designer trainers to sneer at. No fashion tribalism. No poor kid sat out of the class photo because they wore a tracksuit on non-uniform day and got sent home.

There’s evidence this matters. Children from low-income families often dread non-uniform days. Why? Because if you can’t compete in the style Olympics, you’re better off not turning up at all. Uniforms, in this sense, act as a kind of sartorial truce. We may not all be equal, but at least we all look equally uncomfortable.

There’s also the argument that uniforms reduce distraction. A sea of sober colours might help schools feel more like places of learning and less like TikTok catwalks. They can promote safety, too — easier to spot who’s meant to be on site. And sure, for some students, there’s a sense of identity, even pride, in wearing the school crest. Tribalism, social belonging, markers of in-group identification, have their uses.

The case against (Or: “Your identity is not regulation grey”)

But let’s not kid ourselves. Uniforms often don’t come cheap — especially when schools insist on branded blazers, bespoke kilts, or specific shades of “school-issue” black. For families already stretched, that’s not levelling the playing field; it’s moving the goalposts and charging for access.

While some schools work hard to make sure their uniform can be bought in Asda, with iron-on patches and elastic waistbands, others seem to have been designed by someone with shares in a schoolwear supplier.

According to The Children’s Society’s 2020 report, The Wrong Blazer, the average cost of a secondary school uniform in England is £337 per year on school uniform for each secondary school child and £315 primary school children. However, more recent figures reported by The Guardian in August 2024 indicate that parents are spending an average of £422 per year on secondary school uniforms. That includes branded items, PE kit, and mandatory extras like school shoes or regulation bags. And for families with more than one child — or those experiencing in-year growth spurts — that figure can climb quickly.

Then there’s the small matter of autonomy. Teenagers aren’t exactly bursting with opportunities to express themselves. What they wear is one of the few ways they can assert who they are. Telling them they can’t because it might “disrupt learning” is, at best, patronising — at worst, a kind of low-level authoritarianism that teaches compliance over confidence.

And if we’re talking comfort, don’t forget the students for whom polyester isn’t just annoying but actively distressing. Neurodiverse kids with sensory issues? Girls on their periods forced into pencil skirts? It’s amazing how many policies forget that clothes are worn by actual bodies.

When uniform becomes protest

The more schools clamp down on uniform rules, the more protests spring up. Some recent headlines read like parodies: children barred from toilets for wearing the wrong skirt, girls sent home for not meeting a hemline requirement apparently invented by a time-travelling Edwardian.

In one case, the reaction to these policies caused such uproar that students organised walkouts. What’s interesting isn’t just that they protested — it’s that they were right. The emphasis on control over dialogue, on skirts over substance, speaks volumes.

Do uniforms actually improve learning?

The short answer is, no, not really. The EEF states in its toolkit that there is little robust evidence that introducing a school uniform will, by itself, improve academic performance, behaviour, or attendance.

While some studies suggest that uniforms may contribute to improved behaviour and attendance, these effects are often modest and not solely attributable to the uniform policy itself. For instance, a study published in ScienceDirect found no significant differences in social behaviour or school attendance between students in schools with and without uniform policies

There’s some evidence around “enclothed cognition” — the idea that what we wear affects how we behave. For instance, research by Adam and Galinsky demonstrated that participants wearing a lab coat associated with attentiveness performed better on attention-related tasks. However, the applicability of these findings to school uniforms is debatable, as the symbolic meaning of a lab coat differs from that of a school uniform. Your best outfit on a first date probably does more for your posture and self-belief than a logoed sweatshirt ever could.

What is worth noting is who gets hit hardest when uniform policies go wrong: girls, poorer pupils, those who don’t (or can’t) conform. A rigid uniform doesn’t just hide differences, it can magnify them. Uniform policies can disproportionately affect girls, students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and those who do not conform to traditional gender norms. A study in Public Health Reviews highlighted that rigid uniform policies might exacerbate existing inequalities and negatively impact students’ physical and psychological health

There’s also some evidence that uniforms may also restrict physical activity, particularly among girls. A study by the University of Cambridge found that in countries where school uniforms are common, fewer young people meet the recommended levels of daily physical activity, with the disparity being more pronounced among primary school-aged girls

A new uniform for a new age?

Some schools are adapting. At Dame Dorothy Primary in Sunderland, they’ve ditched traditional uniforms for movement-friendly kit — tracksuits, trainers, flexibility. The result? More physical activity, particularly for girls. Less fuss. More comfort. And nobody died from not wearing a tie.

Campaigns like those from Play Scotland and Youth Sport Trust are pushing for uniforms that work with children’s lives, not against them: practical, affordable, inclusive. Imagine that.

Education secretary, Bridget Phillipson, has pledged to lift 100,000 children out of poverty by expanding access to free school meals. Alongside universal breakfast clubs, capped uniform costs, and state-funded childcare. In that vision, a child’s blazer matters less than whether they’ve had anything to eat. It’s not just about comfort or branding, it’s about dignity and whether we want schools to be engines of opportunity, or just places where poor kids get told off for wearing the wrong shoes.

So… what are we wearing?

Uniforms, when you really look at them, are never just about clothes. They’re about something deeper: the values we choose to promote, the ways we exercise control, the identities we expect children to adopt — and, in many cases, the quiet assertion of institutional power.

So perhaps the question isn’t whether uniforms are simply good or bad. That’s too crude, too binary. The real question is this: Are we willing to listen to the students who are most affected by these policies? Because more often than not, they’re the ones with the least say, and the most to lose.

As we rethink what school should look like — and who it should serve — it’s time to ask whether the uniform still fits. Can schools find a better balance between unity and individuality? Between consistency and comfort? Should we be moving toward flexibility, even optionality? And crucially: are we ready to loosen our grip on control and replace it with trust?

We’d love to hear your thoughts. Should uniforms stay or go? Are they a leveller or a leash? What’s your school doing — and is it working? Get in touch and let us know.

I think the gender issue is a huge one in uniform. Girl's uniforms often encode pretty retrograde expectations - particularly in secondary schools, where wearing a skirt and flat ballet pump style shoes actively discourages physical activity in the playground.

Thanks again, David. When I was teaching internationally, our senior classes were free to wear casual dress. Our students consistently achieved in the top ten graduating cohorts in Asia (not just China). It was great having one less thing to enforce and it worked wonders for teacher-student relationships.