To err is human

An Essay on Criticism, Alexander Pope

Making mistakes is an inevitable part of life. We’re all wrong about something at some point. Equally obviously, contending with failure, learning to drag ourselves up by the bootstraps when we fall down and persist in the face of setbacks is part and parcel of human existence. But is making mistakes something to aim for? Should failure be celebrated?

Clearly, in some areas of human endeavour mistakes cannot be tolerated. We are much more tolerant of failure in education than in, say, aviation, because the stakes are so much lower. If we mess things up no one dies. It’s hard to imagine a pilot saying, “If at first you don’t succeed, try try again.”

Despite that, there’s an awful lot of ill-thought out, earnest advice in praise of mistakes and failure out there. Why have we come to eulogise this sorry state of affairs? Why would teachers prioritise getting the answer wrong over getting it right?

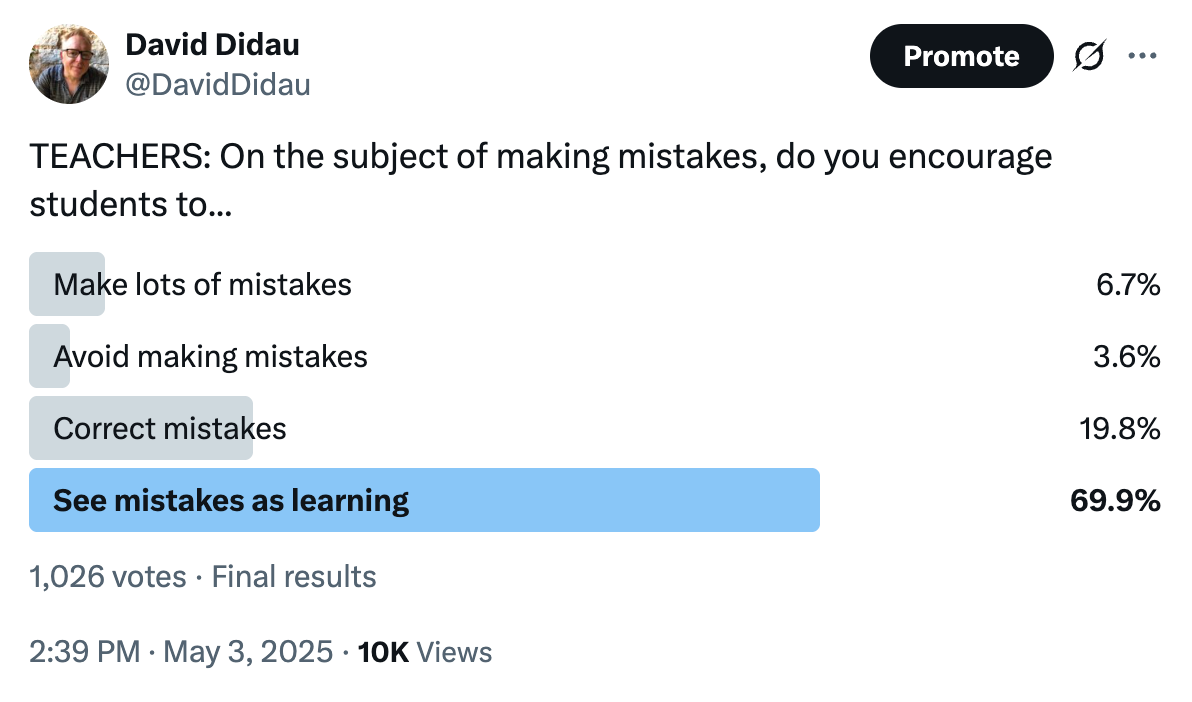

Now, you might think I’m wrong to say that any teachers think this. I conducted a very unscientific survey on Twitter with the following result:

As you can see, almost 70% of the teachers who responded think that mistakes are to be viewed positively, and less than 4% see it as their duty to help avoid making mistakes in the first place. Of course, it would be foolish to read too much into this as we don’t know precisely what the teachers involved really think - we can’t even be sure they are all teachers - but there are definitely people out there who valorise failure and see making mistakes as ‘essential to learning.’

Rather than embarrassing anyone else, it might be fairest to consider some the blogs I’ve written myself. In June 2012 I wrote a post called The Art of Failing in which I said,

Obviously getting something wrong, performing poorly and making mistakes is uncomfortable. But these things are a part of life. An important part. Apart from all the stuff about failure being character forming there’s the more important consideration that if we only ever experience success then maybe we aren’t trying very hard?

I so much believed this to be true that I advocated giving children tasks at which they could not succeed:

You could make the time limits too tight or make the success criteria so impossibly exacting that there is no way they could meet them. Maybe you won’t give them all the required resources or maybe the task is so open-ended and vague that there simply isn’t a solution. Naturally enough, students will find this frustrating. They’ll want to give up. The point is that you need to unpick with them why it’s important to fail. Some students never fail at school; they find everything effortless. Others never seem to do anything else. The point is that working hard despite the chance of failing is difficult. We tend to focus on the product rather than the process. By removing the possibility of there being a successful product we can force students to focus on the process of learning. They will start to see that understanding and valuing the process will lead to the creation of better products and they will begin to see that it doesn’t matter if at first you don’t succeed: you can always fail better in the future.

I honestly thought this was a good idea. Mea culpa. Making mistakes for the sake of making mistakes isn’t something to be lauded, it’s absurd. The truth is that the vast majority of failure is spectacularly unproductive and prodigiously wasteful.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to David Didau: The Learning Spy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.