Culture isn’t a rocket ship: the trouble with compliance and deficit thinking

Why surplus models of school leadership are a better bet for creating a culture where teachers can thrive

This post is a response to Lynsey White’s post Get On the Rocket Ship or Get Out of the Way. To be clear, I don’t know anything about Lynsey or her school and I do not what to criticise her personally. I’m sure she is doing the best she can in what are no doubt challenging circumstances. What follows is a critique only of the ideas expressed in her post.

Culture, we’re told, isn’t declared. It’s lived. Not what’s pinned on the wall, but what’s whispered in the corridor. And fair enough: every school has its eye-rolls and unsaid truths. We’ve all worked in places where the espoused values are about as binding as fridge magnets. What’s less often admitted, though, is that the louder leaders proclaim culture, the more it tends to become a performance.

There’s a popular idea floating round school leadership circles: are staff on the rocket ship with us? If not, the logic goes, perhaps this isn’t the place for them. It’s a compelling metaphor. The rocket ship conjures speed, vision, purpose. It captures the urgency school leaders often feel: there isn’t time to convince everyone; the work is too important. It’s not just about compliance, they say, but about shared belief and clarity of mission. That’s attractive, especially in schools trying to shift embedded habits or raise expectations quickly.

And let’s be fair, there’s truth in this. It’s exhausting to constantly accommodate staff who undermine or obstruct. Schools do need adults who model shared values. There are moments when challenge hardens into cynicism, and when that happens, culture suffers. The metaphor is trying to express a legitimate frustration: we cannot build something excellent if we spend all our time appeasing those who don’t want to build it.

There’s also something valuable in the clarity. The best school leaders do make expectations visible. They don’t hide behind vague mission statements. They say: This is who we are. This is what matters. Are you in? That level of decisiveness is not always comfortable, but it can be powerful. And I’ll admit this too, the metaphor made me stop and think. It clarified how often I’ve watched school leaders quietly tolerate behaviours that chipped away at the culture they were trying to build.

But it’s also why we must be careful.

The rocketship analogy echoes Jim Collins’s mantra from Good to Great: get the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus, and the right people in the right seats. For business leaders in pursuit of growth or market dominance, perhaps that made sense. Perhaps not. It’s worth remembering that Collins’s research, once hailed as gospel in the business world, hasn’t aged well. Many of the companies he singled out as exemplars later faltered or collapsed entirely. The premise was seductive but, under scrutiny, unsound. That should give pause to any school leader tempted to import boardroom metaphors into the classroom. But schools are not corporations. Children aren’t clients. And staff aren’t passengers to be shuffled or ejected according to performance metrics.

Rocket ships, unlike buses, are built for speed. They have a destination, a single direction, and no tolerance for detours. Once launched, you’re either strapped in or left behind. It sounds visionary and exciting, but what are the risks?

The work of education is less about streamlining a workforce, than cultivating a culture where people can grow, not just perform.

Staff who “aren’t on the rocket ship” are framed as a problem. Misaligned, disengaged, or obstructive. But what if that’s a lazy inference? What if the issue is not their attitude, but the way we’ve chosen to read it? Enter the Fundamental Attribution Error: the cognitive bias that leads us to blame people’s character instead of considering context. The member of staff who’s withdrawn? Maybe they’re overwhelmed. The one who questions every new initiative? Maybe they’ve seen ten others crash and burn. What gets mistaken for negativity might simply be realism. More than that, it might be integrity. When “alignment” becomes a euphemism for “agreeing with me,” leadership tends to become doctrinaire.

The problem with deficit culture

The idea that schools should not “carry” staff who are “half-in” is emotionally seductive. But organisationally, it’s dangerous. Culture is not strengthened by shedding people. It is revealed in how we hold them.

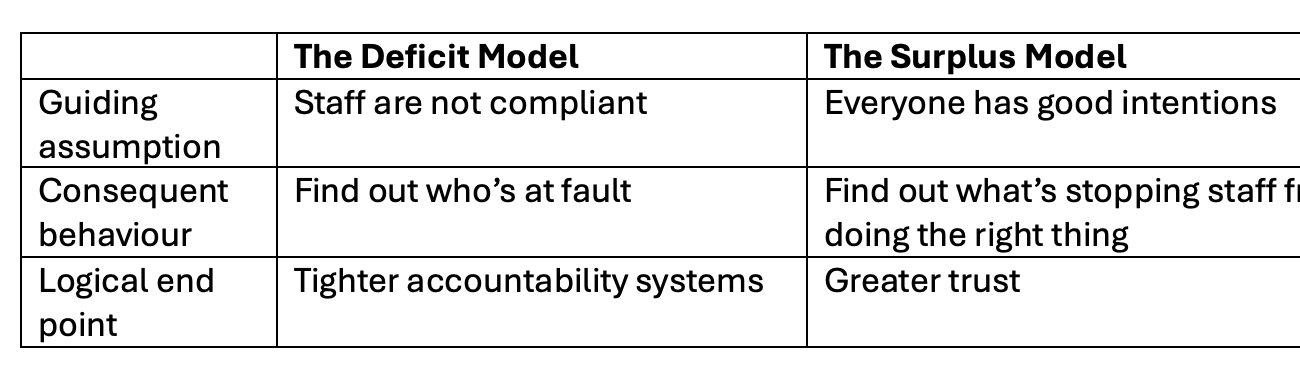

In my book Intelligent Accountability, I discuss two models of school leadership: the deficit model and the surplus model. Schools often seem to be run on a deficit model whereby any deficiencies or failings are attributed to a lack of understanding, information, effort or good will. The efforts of ‘experts’ (school leaders, inspectors, consultants, senior teachers, etc.) who understand what needs to be done are stymied by the actions (or inaction) of non-experts (classroom teachers) who do not. In a deficit model, failings are attributed to the inability of non-experts to understand or enact “realistic budgets, plans and targets”. The deficit model assumes all would be well if only teachers and leaders were more motivated, worked harder or were somehow ‘better’ in some undetermined way. Undesirable outcomes are due to someone’s bad faith, incompetence or lack of skill. To act in this way, school leaders have to believe that teachers know how to teach better but, for some reason, are choosing not to do so.

According to this way of thinking, problems will be solved if these deficits can be addressed in some way. Deficits are dealt with by supplying more information and imposing stricter parameters, tighter deadlines and clearer consequences. If only we could establish responsibility, apportion blame and force everyone into line, success would be guaranteed. This is the logic behind the way much of the education system manages the accountability process: schools and teachers cannot be trusted to do the right thing and take responsibility for their own development, so they need to be coerced with the cudgel of accountability until they fall into line.

When teachers are told to teach in ways they disagree with, the very best we can expect is compliance. One of three outcomes is probable. Teachers will either:

Comply with instructions in the belief that they are unfit to have their own professional opinions.

Play the game but do so resentfully and without real engagement.

Struggle to comply with impossible demands, be perceived as failures and ‘supported’ out of the profession.

In each scenario, students – and particularly the most disadvantaged students who most need effective teaching – suffer. Ultimately, the rationale of the deficit model is to get rid of ineffective teachers and replace them with effective ones. But where will these effective teachers come from? It’s not as if schools are inundated with wonderful prospective teachers clamouring to get into the profession.

Towards a surplus culture

But what if we ran our schools on a surplus model? What if we assumed that teachers were basically trustworthy, hard-working and knew what they were doing? Of course, good intentions are not enough, but an institutional belief that teachers are essentially out to do their best changes institutional culture. Instead of seeking out responsibility and apportioning blame for any perceived failure, in a surplus model the working assumption would be that there must be a systemic impediment preventing teachers from doing the right thing, and if we can only find and smooth out the obstacles, people will naturally do what is in the children’s best interests.

This might sound naive. Every senior leader has worked with teachers who are, for one reason or another, struggling. While such teachers can mostly be supported to improve, there may be a small minority who are too lazy or nefarious to do so. A surplus model doesn’t just ignore this possibility, but it does assume – until proven otherwise – that teachers are well intentioned and responsible. This doesn’t mean leaders should never fire incompetent employees, and it doesn’t mean that senior leaders shouldn’t make tough decisions, but it does mean that we should begin by assuming that everyone has current and developing expertise. If our analysis ends when we identify guilt for making mistakes (or being incompetent), we are less likely to recognise the systemic factors which made these errors possible. Individuals must be accountable for their actions, but systemic failures are the responsibility of school leaders. Understandably, some leaders find it inconvenient to look beyond human error.

Accountability in a surplus model

A sensible surplus model insists that trust is reciprocal and that autonomy is earned. When everyone is seen, everyone is known, and the systems we build make success more likely than failure. Just in case it’s not clear, I’m arguing that the surplus model is more likely to create the conditions for teachers to thrive.

Instead of resulting in ever tighter accountability, such a model produces greater trust. And, when teachers are trusted to be their best, when they are acknowledged as knowing more about teaching their subjects to their students in their classrooms, then they are allowed to select solutions that may be far better than those chosen by less knowledgeable leaders. The more trust and responsibility teachers are given, the more they are empowered to find out what might be more effective, and the more likely they are to achieve mastery.

In contrast to the built-in insufficiency of a deficit model, the surplus model is premised on sufficiency. The constant urge for schools to be better than ‘good enough’ encourages a lack of realism.

The table below suggests other differences between these two approaches.

One of the most bitter ironies is that schools who most need to operate a surplus model – schools considered to be failing – are also those where the risk of doing so may seem untenable. This creates a vicious cycle in which accountability without trust leads to teachers being too fearful to exercise their professional judgement. On the other hand, schools considered successful feel able to risk trusting their staff and, consequently, teachers at these schools are more likely to thrive, leading to further successes.

The risk of rocket ships

But the version of accountability implied in the rocket ship metaphor is something else entirely. It feels top-down, brittle, impatient. It assumes that the leader knows best, and that if others aren’t visibly enthused, it’s because they’re not trying. But as any good teacher knows, performance isn’t always proof of understanding. Just because someone looks aligned doesn’t mean they’re bought in and just because someone isn’t doing what you want doesn’t mean they’re resisting.

It’s true that children have excellent radar. They know which adults are phoning it in. They also know which adults have been cast as outsiders. When leaders foster cultures of implicit favouritism — rewarding visible enthusiasm while quietly sidelining dissent — students pick up on that too. They learn to mimic it.

We might say we want staff who care but sometimes those who care the most are the ones least able to pretend everything’s fine. If we punish that honesty, we corrode not just the team, but the values we claim to uphold.

I’m all for ‘radical candour’ but it’s too often misused. It becomes a get-out clause for poor relational practice. “I’m just being honest” becomes an excuse for bluntness, or worse, self-indulgence. The original idea - care personally, challenge directly - has a second half for a reason. Challenge without care is poor leadership.

It is easier to sack someone than it is to change the system that keeps generating misfits. But no one has ever said school leadership is supposed to be easy.

Of course, some people aren’t doing the job well. Some may be toxic. And some may need to go. But these should be hard decisions, made through rigorous, fair processes. We should agoinise over these decisions and see them as personal failures. A culture built on getting rid of those who face doesn’t fit doesn’t sound like a great culture.

In my experience, the best school cultures aren’t rocket ships. They’re weather systems. Complex, evolving, and often inconvenient. You don’t get to choose the wind. You navigate it. And if you’re serious about your mission, you don’t just fly with those already on board. You make space to bring everyone on board to make the most of eccentricities, to celebrate diversity of opinion and seek out contrary views.

The goal should be to lift off with an elite crew but to lift everyone up.

I’ve written a couple of posts about how systems thinking is maybe the best bet for getting the kind of culture you want in your school.

Applying systems thinking to school leadership Part 1

Over the past few months, I’ve been thinking a lot about how cybernetics and systems management can be applied in schools. If your first thought is to assume that this must have something to do with tech (or Dr Who) you can be forgiven as the term has been thoroughly hijacked since it was first coined by the mathematician, Norbert Wiener in 1948. The word is derived from the Latin (via Greek)

Applying systems thinking to school leadership Part 2

In Part 1 of this series I looked at the idea that ‘a system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets’ and explored some of the more predictable reasons systems go awry. This post will address the idea of systems engineering in a bit more detail and spotlight the work of environmental scientist Donella Meadows.

Totally agree David and try to live out the surplus model as a Senior Leader

...after all Rocket ships by definition take us to places with no atmosphere!

Totally agree and this aligns with my experience in leading change. Shifting assumptions and avoiding universalising the staff as some monolithic group led to a better understanding of why people struggled with change. Much of it was low-confidence in the face of 'superstar' teachers, which led us to start elevating and showcasing the classroom practices that were less 'dazzling', but highly effective and practical. Once that happened, people realised that the shift was manageable and within their control. Lesson learned: show an interest in the motivations of your colleagues. And as my father would say: get your rocket ship back to earth.