Balancing accountability & trust: five principles for effective statutory assessment

Tim Oates argues that national tests should be light-touch, high-trust, and curriculum-aligned in order to keep standards visible without distorting what is taught

In Intelligent Accountability, I argue that genuine improvement in schools depends on designing systems that balance trust and accountability. The accountability process should help us see the system clearly, not punish the people working within it. Applied to assessment, this means distinguishing between feedback that illuminates learning and surveillance that distorts it. Systems fail not because teachers cannot be trusted, but because structures make it easier to look good than to be good. At the system level, the same principle applies. Without intelligent accountability, without clear, proportionate checks on what pupils are learning, the state itself becomes blind.

Statutory assessment exists to prevent precisely this. Its purpose is to provide a shared, objective picture of what children across the country have learned. It allows policymakers, teachers, and the public to see whether the education system is delivering on its promises. More importantly, it keeps curriculum ambition honest. A national curriculum without national assessment risks becoming aspirational rhetoric: fine words with no anchor in practice.

In other words, intelligent accountability and statutory assessment serve the same end: both are ways of keeping ourselves honest. The former ensures that schools remain faithful to the spirit of education, the latter that the curriculum remains grounded in what children actually know.

What can we learn from Sweden?

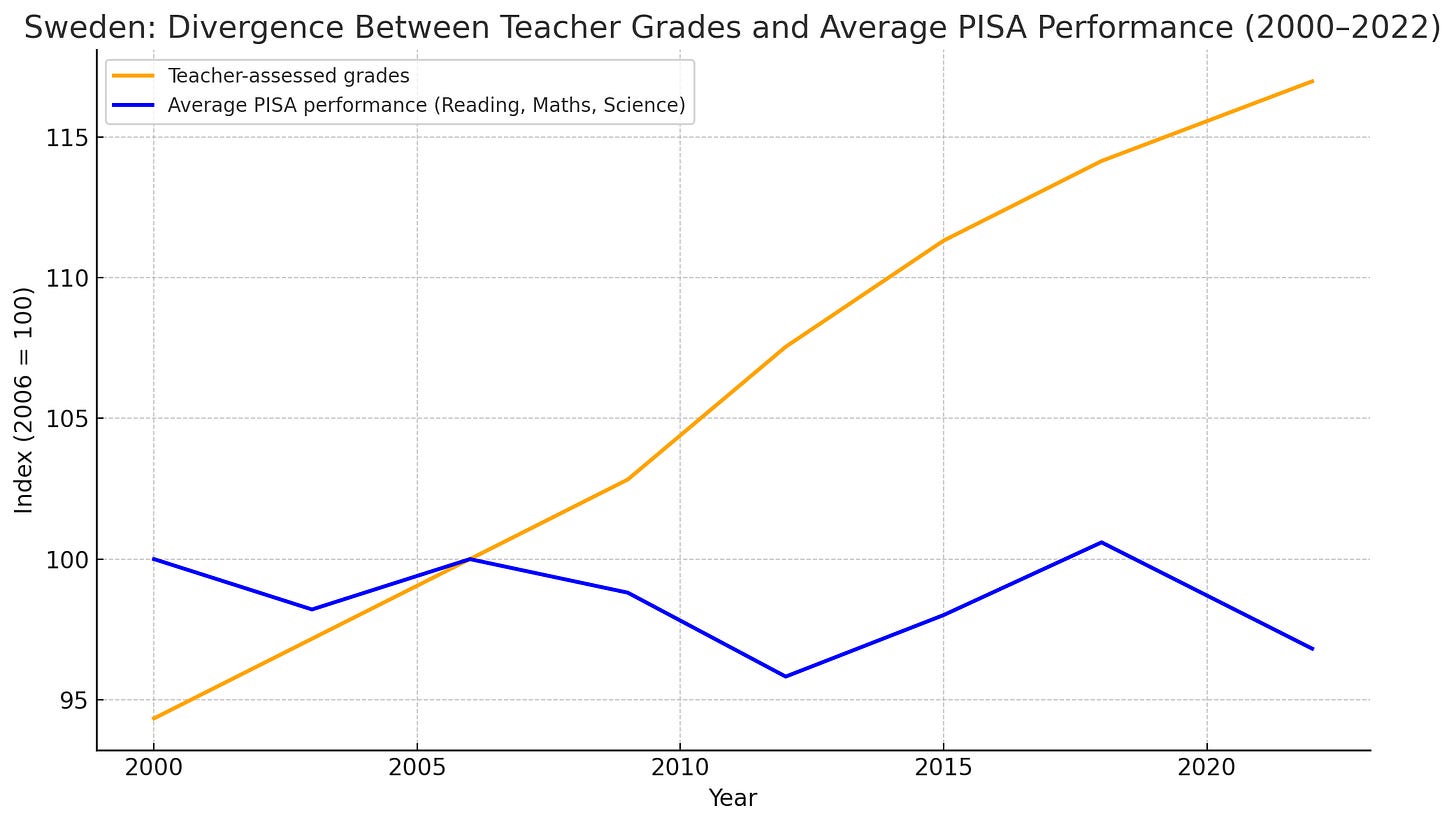

In the 1990s, Sweden dismantled most of its national testing system. Responsibility for assessment was devolved to schools, and teacher judgement replaced external checks. It was a move born of trust: teachers, it was assumed, would best understand their pupils and their progress. Yet within two decades, Sweden’s once-envied education system was in free fall. Results in international surveys such as PISA fell sharply, achievement gaps widened, and public confidence in standards eroded. Subsequent reviews suggested that the absence of robust national assessment had allowed inconsistency to creep in. Grades rose even as attainment fell, and no one could say with certainty what a Swedish child at fifteen actually knew. The lesson was uncomfortable but clear: without statutory assessment, standards drift and trust collapses.

The paradox is that both trends - the rising grades and the falling scores on PISA tests - are symptoms of the same structural change. When teachers were asked to assess their own pupils without national benchmarks or external moderation, expectations began to drift. Most teachers, acting in good faith, graded generously. Sometimes this was to recognise effort, sometimes to reward improvement, and sometimes because higher grades reflected well on the school itself. Over time, small acts of kindness and professional pride accumulated into systemic inflation.

At the same time, Sweden’s curriculum reforms had shifted emphasis from tightly specified content to broad competencies such as communication, creativity, and collaboration. These qualities, valuable in themselves, are far harder to measure objectively. In such a system, it became easy for teachers to award high marks for engagement or participation even when mastery of core knowledge declined. The result was that schools became more internally consistent but nationally incoherent: each teacher applying their own standard of “good enough.”

Meanwhile, PISA was measuring something else entirely. Its tests assess the ability to apply learned knowledge to new and unfamiliar problems. As grade standards drifted upwards and content knowledge thinned, Swedish pupils appeared to be performing better in their own schools but worse by international comparison.

The lesson is uncomfortable but clear. Trust without calibration corrodes standards. A system that relies wholly on teacher assessment can create a comforting illusion of success while real substance quietly ebbs away. Without shared reference points, fairness falters, and the link between effort, knowledge, and achievement begins to blur. In Sweden’s case, the move intended to honour professional trust ended up eroding the very trust it sought to build.

Keeping the system honest

The purpose of statutory assessment is prevent what has happened - and is still happening in Sweden - from happening here, by providing a shared, objective picture of what children across the country have learned. By doing so, it allows policymakers, teachers, and the public to see whether the education system is delivering on its promises. More importantly, it keeps curriculum ambition honest. A national curriculum without national assessment risks becoming aspirational rhetoric—fine words with no anchor in practice.

In England, this alignment can be seen most clearly in the phonics screening check (PSC). When it was introduced in 2012, many dismissed it as reductive. Yet its effect was unmistakable: schools began teaching systematic phonics more consistently, and reading standards rose sharply in the years that followed. The test didn’t teach children to read, but it made visible whether the national curriculum’s early reading expectations were actually being met. Similarly, the reformed Key Stage 2 SATs ensure that pupils’ grasp of grammar, punctuation, and mathematics is broadly consistent across the country. Without them, it would be impossible to know whether improvements in local test scores or teacher judgements reflected real gains in learning or simply local generosity.

Conversely, when national assessment is removed or weakened, ambition tends to drift. The early 2000s saw a period when teacher assessment replaced formal testing at Key Stage 3. Within a few years, evidence from Ofsted and the National Strategies suggested that subject standards were becoming increasingly uneven. Schools could no longer compare progress meaningfully, and expectations for what pupils should achieve by fourteen began to slide. In effect, what wasn’t measured stopped being taught with the same rigour.

Statutory assessment keeps such drift in check. It ensures that what is written in the national curriculum is, at least in principle, what is taught in classrooms. It provides comparability over time, allowing us to tell whether a rise in grades represents genuine improvement or a shift in marking standards. Without consistent benchmarks, the signal of learning is lost in the noise of local interpretation.

What statutory assessment looks like

In England, statutory assessment refers to the nationally mandated tests and examinations that punctuate key stages of education: the phonics screening check in Year 1, the multiplication tables check in Year 4, and GCSEs at sixteen. These assessments sit at the intersection of curriculum, accountability, and public trust. They provide a shared set of reference points—moments when the state pauses to ask, “Are children learning what the curriculum intends them to?”

Each serves a different purpose. As we’ve seen, the PSC verifies whether children have secured the alphabetic code needed for fluent reading. It consists of forty words, half of them pseudo-words such as ‘splog,’ designed to ensure decoding rather than memorisation. The test’s power lies not in its content but in its signal: it revealed that before its introduction, many children were progressing through school unable to decode unfamiliar words, even when their reading levels appeared satisfactory. Once schools had access to this new information, teaching practice changed.

The multiplication tables check, made statutory in 2022, plays a similar role for mathematics. Its purpose is to confirm that pupils have committed the multiplication facts up to 12×12 to long-term memory. The online, quick-fire format is deliberately brief—twenty-five questions in under five minutes—but its implications are significant. Fluent recall of times tables frees up working memory for more complex reasoning and problem-solving. By making this knowledge check national, government can ensure that every child receives the same expectation of fluency, and that gaps in foundational number knowledge are identified early.

Other countries use statutory assessment differently but with a similar logic. In Japan, for instance, national assessments are administered periodically to a sample of pupils rather than every child. The goal is to monitor system health without overwhelming schools with testing. In Finland, external assessment is limited but tightly aligned with a highly coherent national curriculum, and moderation between schools is meticulous. And in Singapore, where teacher judgement is trusted but externally calibrated, national exams are used to maintain precision and fairness, not to drive fear or competition.

These examples illustrate why statutory assessment provokes such controversy. When designed well, assessments serve learning by clarifying expectations and exposing weakness. When designed poorly—or when their results are used punitively—they distort teaching and narrow the curriculum. This is the tension Tim Oates has spent much of his career trying to resolve. His argument is not that statutory assessment should be abandoned, but that it should be light-touch, high-trust, and curriculum-aligned: rigorous enough to secure confidence, but restrained enough to avoid strangling the curriculum it exists to protect.

The problem with high stakes

It helps to distinguish between statutory and certificated assessment. Statutory assessments are those required by government to monitor national standards and system performance. They are universal, often taken by whole cohorts, and their results feed into public accountability. Certificated assessments, by contrast, lead to formal qualifications such as GCSEs or A levels and exist primarily to certify individual attainment. In England, however, these tests are made to serve both purposes at once: they act as statutory checkpoints for the system and as certificated qualifications for pupils. This dual function is what makes them problematic.

When the same test is used to certify individuals and to hold institutions accountable, pressure builds. For pupils, GCSEs determine the next stage of their lives; for schools, they determine inspection outcomes, league table positions, and reputations. Under such strain, the purpose of assessment inevitably begins to warp. Teachers feel compelled to prioritise what is examinable rather than what is most educationally valuable. Curricula narrow, lessons become rehearsals, and pupils are drilled to perform rather than to understand. The test, intended to measure learning, becomes the object of learning itself. Meanwhile, policymakers use the results to monitor national performance, despite the distortions that high-stakes accountability inevitably introduces.

Oates’s alternative vision

Few people have influenced the international understanding of assessment as much as Tim Oates. As Group Director of Assessment Research and Development at Cambridge University Press & Assessment, and chair of the panel that reviewed the National Curriculum in 2011, Oates has spent decades at the centre of the debate about what testing is for. His work bridges research, policy, and practice, and he is perhaps best known for his insistence that the curriculum - not the exam - should be the engine of education. Again and again, he has argued that when assessment drives the curriculum, teaching becomes mechanistic and shallow; when curriculum drives assessment, learning deepens and coherence is restored.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to David Didau: The Learning Spy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.