Applying systems thinking to school leadership Part 1

A system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets

Over the past few months, I’ve been thinking a lot about how cybernetics and systems management can be applied in schools. If your first thought is to assume that this must have something to do with tech (or Dr Who) you can be forgiven as the term has been thoroughly hijacked since it was first coined by the mathematician, Norbert Wiener in 1948. The word is derived from the Latin (via Greek) kybernetes, meaning ‘steersman.’ The French, cybernetique, is the ‘art of governing.’ In this original context, cybernetics – or, to give it its full title ‘management cybernetics,’ was concerned with the design and implementation of effective and efficient systems.

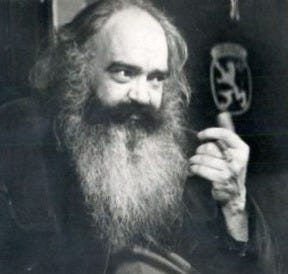

One of the figures most closely associated with the development of cybernetics was the improbably bearded, Stafford Beer, now probably most famous for his axiom ‘The purpose of a system is what it does,’ commonly referred to as POSIWID.

At first glance, this may seem banal, but the point Beer makes is that the purpose of a system is not what you intend it to do or what you hope it will do but what it actually does.

[T]he purpose of a system is what it does. This is a basic dictum. It stands for bald fact, which makes a better starting point in seeking understanding than the familiar attributions of good intention, prejudices about expectations, moral judgment, or sheer ignorance of circumstances.

Stafford Beer (2002)

Or, as Milton Friedman put it, “One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results.”

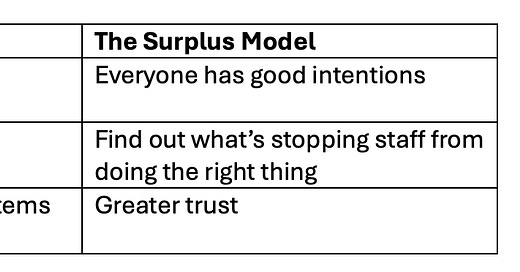

In my book Intelligent Accountability I discuss two models of school leadership: the deficit model (things go wrong because staff don’t follow instructions) and the surplus model things go wrong because there are systemic obstacles preventing good people from doing good things):

My argument is that elements of these models can be found in all schools but some tilt more towards thinking in terms of deficits whereas others think more in terms of surpluses. The deficit model seems rational within a larger system where school leaders don’t feel trusted by the inspectors or government officials but most people, given the choice, would prefer to work in a system guided by the surplus model.

The surplus model is focussed on identifying faults in systems rather than faults with individuals. As we’ve all experienced, sometimes systems unintentionally make it harder to for people to do what’s best. Take the example of the Consequence System for behaviour management:

The intention is obviously that students’ behaviour improves but an unintended consequence is that the system is so onerous that teachers avoid using it. And, although school leaders are often at pains to say that if students have done something particularly dangerous teachers are not expected to cycle through each of the stages, but this is often how it is perceived, both by teachers and students. Another unintended consequence is that students sometimes feel they are allowed to do the wrong thing multiple times before any meaningful consequence is applied.

If the purpose of a system is what it does, the purpose of this system is to give students tacit permission to misbehave and create obstacles to teachers upholding high expectations.

Consider your school’s systems for behaviour, homework, marking, attendance and so on. What is actually achieved? What do teachers and students actually do? If you have a homework policy which results in teachers setting less homework or students doing less homework you have created a system which incentivises perverse behaviour. This is no one’s fault: the fault is with the system.

Why systems go wrong

Systems go wrong in predictable way and for predictable reasons. The first and most obvious reason is that they are poorly designed with little or no though given to user experience. Anything that requires someone who is already very busy (i.e. teachers) to spend time on something where the gains don’t appear worthwhile is likely to fail. This is not because teachers are lazy or untrustworthy but because they’re busy. They already have something pressing and important to do (teach children) and if you ask them to stop doing that you need to give them both an excellent reason and a fairly immediate pay off.

Understanding desire paths

Anyone designing systems needs to think about how human beings want to behave. Most us want to minimise effort and maximise reward. This is why we tend to follow ‘desire paths’ in preference to those laid out by town planners. In the image above, whoever was responsible for laying out the paths ignored the human desire to get to our destination as quickly and easily as possible.

Alternatively, rather than putting in pavements when new buildings were erected, Michigan State University waited for students to create their own paths. The lesson - watch how people behave and design your system around them - can be applied to the systems we create in schools.

An obvious example is the one-way systems that unintentionally make students walk much further to lessons. Consider uniform policies that ignore students’ comfort and preferences. School staff spend endless hours trying to get students to do up top buttons, tuck in shirts and wear skirts at an acceptable length. It’s reasonable to ask whether this is worth the effort when making small tweaks to the uniform might result in less resistance.

The lessons we should learn from desire paths”

Observe first, design second: Watch where people naturally ‘walk’, try to work out why, then build structures around those behaviours.

Don’t punish the path, understand it: If students (or staff) consistently break a rule, the issue may be the rule.

Design for flexibility, not rigidity: Systems should support the rhythms of human needs and routines.

When well-intentioned systems clash with predictable human behaviour, conflict is inevitable. Well-designed systems take into account the shortest route between two points, the path with less resistance and workflow that saves time or effort.

Plan to adjust: the need for constant maintenance

Systems steer our behaviour in ways that can be beneficial or detrimental. From this observation it shouldn’t be too great a leap to think about the various systems we rely on to manage schools. Whenever we see teachers, school leaders or pupils doing something that appears, on the face of it, a bit odd, we should look at the systems that might be channelling their behaviour.

In an endorsement for Intelligent Accountability, Dylan Wiliam wrote the following:

While there is widespread agreement that it is reasonable that teachers, schools and education authorities should be held accountable, what, exactly, accountability really means is rarely spelled out. As a result most accountability systems are either so loose as to be useless, or, at the other extreme, are so tight that they make it difficult, or even impossible to do what’s needed to improve education, and can even produce perverse incentives that lead those working in the system to do things that are good for them, but counterproductive for their students.

The tighter and more prescriptive a system is, the greater the danger it may lead to perverse incentives. The looser and less prescribed a system is, the greater the risk of lethal mutations. Either way, systems always run the risk of causing unintended outcomes and so require constant maintenance.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to David Didau: The Learning Spy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.